Law & Disorder: Confessions of a District Attorney (Authorized 2023 Edition) by Michael Bradbury memorializes his thirty-plus year career as a Ventura County prosecutor, twenty-four as the elected boss of that office. “Disorder” and “Confessions” in the title aptly suggest a legal vocation within a mise-en-scene of chaos and turpitude reminiscent of Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction film. The protagonists, however, are not felonious actors; they are functionaries of the legal system. In this regard, the author details the corrupt acts of judges to cops, who commit adultery, gratuitous violence, dubiously extract confessions, and cover up the sins of their own whenever possible in the pursuit of serial rapists, thieves, and psychopathic killers. The circumvention of the law by people charged to enforce it blurs an imaginary thin line that separates order and madness. For example, Bradbury (and his ghost-writer as he uses the first-person plural) chronicles stories from the point of view of a person dedicated to the discretionary prosecution of offenders, while brazenly admitting how “Oldtimer” officers of the past experienced little to no institutional training and conducted their duties with above-the-law impunity while they mentored newer colleagues.

Bradbury’s Manichean narrative also provides readers with an insight into the mentalité of a prosecutor who imagined himself a cowboy sheriff. A Rooster Cogburn of True Grit if you will. The book states as much and features images of the author costumed as a cowboy at his “HANG ‘EM HIGH” ranch. In this Louis L’Amour-styled narrative, few angels exist on either side of the law as scrupulous cops, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges regularly close their eyes when their colleagues do wrong. Indeed, the author confesses how honest cops and prosecutors dared not break a code of silence that protected their own from being indicted for in flagrante delictos of drunk driving, enhanced interrogations, and the gratuitous use of force on people deemed the “bad guys.”

For example, when a handcuffed narco-trafficker, named Batista, resisted humiliation, Oxnard police officers took turns meting out abuse with the butts of their shotguns until he collapsed into unconscious submission. And when Ron Liesse, a young Ventura police department detective, followed his conscience to testify in a state attorney general investigation against coworkers suspected of a botched premeditated assassination attempt of a serial burglar, he was so ostracized by his department peers he committed suicide.

In both instances, Bradbury did not break the code of silence.

As to the rights of the accused, if the author had his way, he would abolish bothersome Miranda and other Bill of Rights protections. And he is particularly critical of judges as he views them as generally lenient and overly concerned with the rights of defendants. Even though a healthy number of judges historically graduate from the ranks of prosecutors.

Throughout his confessions, the author pruriently objectifies women. It is as though he is trapped in a time warp when such lurid sexism was acceptable as part of a boys-will-be-boys culture. Bradbury, moreover, describes how judges habitually engaged in sex trafficking, dated grand jury members, and encouraged male lawyers to select women jurors deemed attractive for them to ogle during trials. And there is the affair of two Thousand Oaks detective partners, Teddy and Leah, married to different people, who completed one of their regular assignations while on a stakeout of a drug dealer, Raul Mendoza, only to be inadvertently audio recorded and listened to later by prosecutors in the preparation of evidence against the suspect. To avoid exposing the two detectives’ sexual relations, Bradbury delayed the case’s prosecution. Ultimately, the author dropped the charges against Mendoza as he was convicted in Arizona for drug dealing and sentenced to 10 years in prison. So, the affair of the two detectives—one married to an LAPD lieutenant and the other whose wife recently delivered a baby at the time— remained a secret until the publication of this book.

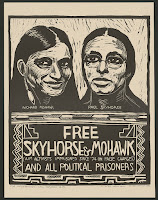

Bradbury contends that the stories in his book are factual and accurate. If so, they are not complete. I was alerted to factual omissions made in Bradbury’s book by Moses Mora (a Native of Ventura, US Army Vietnam Veteran, and social justice activist) concerning chapter Eight on the case of Paul Skyhorse and Richard Mohawk, Native persons who were members of the American Indian Movement (AIM). Wanting to learn of the nexus of the Chicano movement in Ventura County with Native Americans, I interviewed Mora and compared Bradbury’s book with the existing literature on the subject. I also attended a May 3rd conversation between current District Attorney Erik Nasarenko and Michael Bradbury on the book before a standing-room audience at the Museum of Ventura County. Although the two did not discuss the Skyhorse and Mohawk case at the event, Bradbury did highlight several of the stories featured in this review and others with a similar tendency and concupiscence.

Nevertheless, in 1974, the Ventura County DA charged Skyhorse and Mohawk with the October 10, 1974 murder of cab driver George Aird at Box Canyon near Simi Valley. Bradbury argues with vexation that Skyhorse and Mohawk, initially representing themselves, effectively stalled the case with pre-trial motions in order so the prosecution’s key witness, Maruffo, diagnosed with brain cancer would transition before being able to testify against them. Lasting nearly four years, the case was ultimately moved from Ventura County upon the motion of the defendants. While Skyhorse and Mohawk believed they could not get a fair trial in Ventura County, Bradbury indignantly contends that the defendants wanted the move because not guilty verdicts were more likely in Los Angeles due to court juries there being filled from pools of “dregs” and the “flea-bitten."

What Bradbury omits from his account, however, is that the trial was changed to Los Angeles after the defendants proved that at a March 1977 Ventura County Bar Association dinner, with the presiding judge and prosecutor in attendance, several attorneys performed an act titled “The People vs. Tonto” that mocked the case’s protracted pre-trial motions. Michael Leroy Oberg, a distinguished professor of history at the State University of New York-Genesco, states in an electronic essay titled The Murder Trial of Richard Billings Mohawk and Paul Durant Skyhorse “This poorly-thought out bit of racist humor—acted out as AIM activists protested outside—made it seem clear to many that the proceedings could not continue in Ventura County. The California Bar Association called for a change of venue, which was granted.”

Bradbury also omits the fact that Holly Broussard, Marvin Red Shirt, and Marcella Eagle Staff hijacked Aird’s cab on their way back to Box Canyon on the day of the murder. Upon their arrest, all three had Aird’s blood on their clothes; Eagle Staff had the key to the cab in her pants. No physical evidence implicated Skyhorse or Mohawk nor were they in the cab. Accordingly, the Ventura County DA charged the three with the kidnapping, robbery, and murder of Aird. The counts against them were subsequently reduced after they agreed to testify against Skyhorse and Mohawk. The prosecution’s case eventually crumbled not because Maruffo died from cancer before he could testify in court but due to Broussard, Red Shirt, Eagle Staff, and other witnesses such as Carmen Fish and Skyhorse’s spouse Marilyn recanting their statements. Prosecution witnesses Broussard, Eagle Staff, and Marilyn Skyhorse testified in court that they made their initial statements under the duress of law enforcement. Red Shirt further undermined the prosecution’s case when he testified on the witness stand while severely intoxicated—to the point that the presiding judge was baffled how Red Shirt remained upright—as well as contradicting statements he made before the trial. But Bradbury does not make mention of this.

Bradbury does write about the close involvement of the FBI via informants, operatives, and agent provocateurs in the case. A point that the judge of the case would not allow the defense to introduce. This was important as Skyhorse and Mohawk argued that they were framed by the FBI to smear the legitimacy of AIM as part of its neutralization of the organization’s human and civil rights struggles, and probably more importantly cutting off the philanthropy of its supporters. Mora, who worked for the Skyhorse and Mohawk defense, asks the trenchant question who in the Ventura County District Attorney’s Office decided to reduce the murder charges against Broussard, Red Shirt, and Eagle Staff to convict Skyhorse and Mohawk? This is a crucial question as the COINTEL program of the FBI sought to “neutralize” (read destroy) the social justice movements of not only AIM but also Dr. Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Chicanos like the Brown Berets, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, and women’s movements in different parts of the country during the 1960s and ’70s under the directorship of J. Edgar Hoover, a person Bradbury idolizes.

Law & Disorder is an essential book for persons interested in the character and operations of our criminal justice system, despite the often superficial and partial way Bradbury details them. As there are many sides to a story beyond those of a prosecutor. The author also fails to interrogate points of ambiguity as he did about abortion cases he was charged with in 1967 and the vile conduct of one of his deputy DA colleagues. Furthermore, Bradbury refuses to recognize his complicity in undermining the integrity of the administration of justice when he details how he stood by when his peers blatantly broke the law or engaged in unethical acts. This is particularly critical when he expresses a binary worldview defined by “good guys” or “good cops” versus “the bad guys” while not recognizing the existence of “bad cops.” Former Governor Pete Wilson, in writing the forward of the book, recognizes this ambiguity when he states “It [Law & Disorder] teaches us more about human nature than the finer points of criminal law.” Hence, people in law enforcement can be as extremely human as the criminal suspects they chase.

In conclusion, although the author comments in passing on chauvinistic policing in two parts of his book, he completely shies away from discussing race as the central source of historical antagonism of Black and Brown people with white-dominated agencies of law enforcement. This is a critical, accurate, and factual omission on the part of the author. As a result, I recommend this book to be read with ruthless criticism.

C/S

fpb