Friday, December 22, 2017

California History Winter 2017: Defiant Braceros

California History WINTER 2017

Mireya Loza, Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual, and Political

Freedom. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016. 237 pages. $67.80.

Defiant Braceros advances a conversation, if not a charge, of self-definition by many scholars in Chicana/o Studies. Born of a movement of the 1960s and ’70s, academics in this area of study—many with bracero lineage, as has Mireya Loza—committed themselves to the dismantlement of myths that characterized people of Mexican origin as tractable, apolitical, and, in sum, defeated. Some researchers today contend that this epistemological struggle has been waged and completed. This is not the case; typecasts of all sorts run a cycle; so, a new generation of historians, such as Loza, and students, respectively, need to educate as well as be educated of the agency of Mexican-origin communities in the United States prior to and since el movimiento Chicana/o. Today more than ever.

In this regard, Defiant Braceros belongs to an emergent body of literature that scrutinizes the impact of the guest worker Bracero Program upon families and communities in and outside of Mexico in relation to their struggle against forces of oppression. Earlier books, initiated to a great extent by activist-scholar Ernesto Galarza at the start of the second-half of the twentieth century, concentrated on guest worker bilateral agreements between the United States and Mexico since WWII as well as how the agricultural industrial complex manipulated the Bracero Program to economically pit imaginary pond-like braceros against domestic agricultural laborers.

Mireya Loza’s important contribution, however, defines a tradition of bracero subjectivity by way of defiance and deviance. In other words, protean bracero narratives, the author convincingly argues, deviate from as well as defy notions of them as “ideal” (5) tractable, disposable workers. These well contextualized stories also analyze inconsistencies among braceros in relation to their mutable resident status, indigenous-mestizo racial identity, and sexuality as opposed to the normative dutiful father abroad, loyal to Mexico lindo as they labored honorably in the United States. In the exploration of agents secondarily linked to the bracero odyssey, Loza aptly integrates the transnational influence of women as: wives who sought estranged husbands, migrants to border sites such as Mexicali, paramours, granddaughters, and sex workers in both countries. In this regard, the author does not limit this study to the historical as Loza reviews the recent past as multigenerational family members in both nations pursued monetary redemption via the Bracero Justice Movement for ten percent of wages not paid by the Mexican government to superannuated braceros.

In the explication of defiance and deviance, Loza successfully proved the book’s thesis of multiple narratives that defined the lives of Braceros and their communities. Loza’s first example consisted of indigenous immigrants from central Mexico who deviated from the state’s mestizo project of the early twentieth century that advanced a whitening, if not an erasure, of the Indian by ways of cultural and economic assimilation. Hence, Mexican elites viewed the Bracero Program as an opportunity in which to modernize the Mexican Indian—and state—to an ideal mestizo community. In addition to the acquisition of modern technologies, attire reified this catechism. One example consisted of the bracero’s conversion from the use of huaraches (sandals) to boots, or the more complete sartorial style of the urban dandy who relinquished white cotton pantalones de manta (37).

Who was a bracero also depended on the context as the label itself defied official distinction. Before and after World War I, any Mexican national who migrated to work in the United States, largely but not limited to agriculture, were viewed as braceros by employers, detractors, as well as themselves. During World War II, policymakers of the two nations extended the bracero appellation to government sponsored guest workers. Then there were defiant braceros who skipped out of their contracts to chase higher wages, adventure, and freedom; this attained them, along with compatriots who entered the United States without such sanction from the start, the “wetback” slur.

To protect the interests of braceros and domestic agricultural workers in the United States, the Alianza de Braceros Nacionales de México en los Estados Unidos (the Alliance of Bracero Nationals of Mexico in the United States), led by José Lara Jimenez and José Hernández Serrano in Mexico, and Galarza’s National Farm Labor Union partnered for a short-lived period. This endeavor ultimately failed due to its neutralization by the Mexican government. In the process, however, the three and their constituents resented how undocumented immigrants, many apostate braceros, undermined their cause. As a result, defiant ex-braceros who skipped from their contracts, and those who never enjoyed any, found themselves labeled epaldas mojadas (wetbacks) by the Alianza leadership, Galarza, whites, as well as Mexican Americans and long-term Mexican immigrant nationals in el norte. Although Loza touched upon the deviance between Indian braceros vis-a-vis “ideal” mestizo workers, at least in the eyes of the Mexican state, the racist undertone of the “wetback” epithet could have been interrogated further. For example, did Galarza and Mexican American leaders use the wetback smear with the same animus as whites? And how similar or different was the enmity behind the use of this invective by the leadership of the Alianza toward undocumented workers?

The epilogue of Defiant Braceros details the contradictions that undergirded the National Museum of American History’s creation of “a consortium of institutions to preserve the history of bracero communities in Mexico and the United States.” (171) This Bracero History Consortium then embarked upon a Bracero History Project composed of a Bracero History Archive and an exhibition by the museum in Washington, D.C. and others that traveled the nation. The content of the archive and the exhibits did not align, however. For example, the archive evinced the defiant and deviant complexities inherent of the program. Exhibit curators, however, were politically careful to commemorate the ideal tractable bracero as a happy, dutiful father, who honored his guest worker contract then repatriated. The bracero who straddled the immigrant status of the authorized and unauthorized, and partook in actions of deviance and pleasure could not be a part of this official narrative. This would undermine any revival of a similar guest worker program in the future, especially under the administration of President George W. Bush.

Defiant Braceros is thoroughly researched with an even combination of primary source material and secondary literature. From this foundation of oral history interviews, letters, government documents, and seminal books, Loza methodically scrutinizes how braceros and their families coped with forces larger than themselves in a clear and incisive manner. To seamlessly move this trenchant narrative along from one chapter to the other, the author inserts cogent biographies titled Interludes. Loza also pacts each chapter with shrewd analysis. So much so, that many of the topics covered (such as the Bracero Justice Movement, the Alianza-Galarza connection, and others) will surely inspire graduate students and scholars alike to develop monographs based on them.

In closing, upper-division undergraduates, graduate students, and researchers will find Defiant Braceros a fount of knowledge on the lives of people previously viewed as agentless players of the past.

Frank Barajas

California History WINTER 2017

Sunday, November 12, 2017

A Unicorn

At a teaching demonstration for a tenure-track faculty recruitment, students sat in a jammed classroom, a good number enrolled in sections of Chicana/o Studies. The visage of the candidate reflected a Mayan Mexican ancestry. Awestruck, one collegian who matchedthe indigeneity of the presenter (as did many others in the audience) hung on every word pronounced by the presenter. The student spied a unicorn—or the reappearance of the foremost American of this continent with a Ph.D. This person’s riveted countenance, nearly tearful, revealed the deliverance of the possible self. I know this. How? Because since my early years in academe—first at Moorpark College, through my matriculation at CSU Fresno, the Claremont Graduate School and my first gig at Cypress College and now here—I’ve experienced this wonder that we progeny of the Maya, Purepecha, and Tarahumara (not the all too prolific Cherokee from “great-grandma”) can also, and must, impart our epistemology and stories in meaningful numbers, not just as unicorns.

C/S

fpb

C/S

fpb

Tuesday, August 8, 2017

Chicanas and Chicanos on the Storm

Pacific Coast Branch-American Historical Association

CSU Northridge, Saturday August 5, 2017

Frank P. Barajas, California State University Channel Islands

Session VII: 1:30-3:00 pm. Panel 58. Ventura County’s Ethnic Histories

“Schools, Spaces, and Subjects: Chicanas and Chicanos on the Move”

Project Origins and Scope

My current project opens where Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard California, 1898-1961 (2012), my first book, finished.

From the start of the 1960s, it tracks the emergence of the crusade of Chicanas and Chicanos in Ventura County as part of a larger regional and national movement. It argues that Chicanas and Chicanos of the Sixties and Seventies in this Southern California locale expressed a politics distinct from the Mexican American Generation that came of age largely within the years of the 1940s and ’50s. Although young men and women of the Chicana and Chicano generation demanded similar reforms in education, housing, labor, and law enforcement as did many of their mentors, this set of youths expressed an exigent militancy. In this regard, I have three

potential titles that highlight the manuscript’s thesis. The first signals the work as a follow up to Curious Unions. It is Curious Insurgents: The Chicana/o Movement in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975. The other two employ poignant reflections drawn from the oral history testimonies of two Chicanas that articulate the audacity of young men and women of the period. They are Mexican Americans with Moxie: The Chicana/o Movement in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975 and Chicano On!: Mexican Americans with Moxie in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975.

In a 2013 interview, the noun moxie in the second title emerged from a pensive moment of Diana Borrego-Martinez who graduated from San Fernando Valley State College in 1972 (now CSU Northridge or CSUN) with a Chicano Studies degree. Borrego-Martinez was raised in the Ventura County community of Santa Paula. Rodolfo F. Acuña in his 2011 book The Making of Chicana/o Studies: In the Trenches of Academe described Borrego-Martinez, and approximately a dozen her peers, as “hard core” United Mexican American Students (UMAS) club members. After the conversation on the protests and arrests of the time in which she partook, she stated, “You know, we had moxie.”

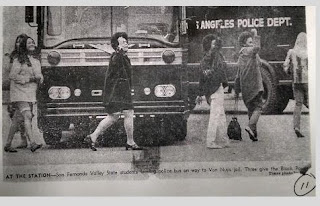

(Diana Borrego-Martinez far left. Jan. 10, 1969, Los Angeles Times)

Chicano On! arose from an email’s complimentary close that followed an oral history interview with Paula Muñoz in 2016. Muñoz grew up on the Avenue in the City of Ventura and attended Ventura College before her transfer to CSUN in 1972. The phrase Chicano On! not only encapsulates the radical chic of the time but also suggests the notion that el movimiento continues to the present despite that much of the literature details a late-1970s/early-1980s requiem. At this point, my choice for the book’s title is the last as it incorporates notions of a generational becoming, fashion, and dialectical struggle. In addition, Chicano On! conveys the resolute agency of people of Mexican origin (the U.S. born as well as documented and undocumented immigrants) who crumbled dominant stereotypes of this demographic as passive, apolitical, educationally disinterested, and civically disorganized. To market the project, the subtitle also suggest the geographic and temporal mise-en-scene. Furthermore, “with moxie” speaks to how Chicanas and Chicanos of el movimiento were the activist progeny of the Mexican American Generation but with an octane indicative of the period’s larger movements of civil rights and de-colonialism. Both generations, however, worked simultaneously and informed each other while they often differed on strategy—a dynamic downplayed in the current literature.

Moreover, the historiography of the Chicana/o Movement revolves largely around the more nationally recognized, male-centric movements of Cesar Chavez’s farmworkers, Sal Castro and the student blowouts in East Los Angeles high schools, Reies Tijerina’s revanchist pursuit of New Mexican land grants, and the struggle for social and political self-determination by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and Jose Angel Gutierrez in Colorado and Texas. Such events, as in the case of the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium of August 29th 1970 against the war in Vietnam, attracted the support of fanatics from different parts of the country—even Kansas in the words of Alurista—in protean degrees and times. Consequently, this project elevates Ventura County subjects from the shadow of the metropolis of Los Angeles while it contextualizes its actions as part and parcel of such national currents.

Another facet consists of the geo-political position of Ventura County Chicana and Chicano youth. For example, to the north existed the University of California at Santa Barbara, the fount of El Plan de Santa Barbara of 1969 and schematic for the creation of Chicano Studies in and out of academe. El Plan charged students to recruit family and peers from the schools in their communities as well as afar. Then there were the institutions of San Fernando Valley State and the University of California at Los Angeles to the southeast. Both campuses recruited the underserved from Ventura County schools to the cells of activism in Los Angeles County. Conversely, UCSB attracted students such as Mayo De La Rocha of Roosevelt High School in East Los Angeles who networked with transfer students from Moorpark College and Ventura College. Many participants of the 1971 La Marcha De La Reconquista from Calexico to Sacramento, such as Yvonne de los Santos of Saticoy, were recruited by activist college students from their barrios and colonias.

(Yvonne De Los Santos, middle, image UC Santa Barbara)

(Google Maps)

Once matriculated at one of the community colleges or public universities of Southern California, Ventura County youth found themselves transformed, if not radicalized, by clubs such as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Student Union (BSU), UMAS, and later El Movimiento Estudiantíl Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). This happened as they witnessed white and black peers of SDS and the BSU, respectively, protest the war in Vietnam, racist acts on campus, and the omission of a curriculum that recognized their history. In one instance, in mid-October of 1968 Chicana and Chicano students at UCSB—many yet to be politicized—witnessed BSU students annex North Hall, the building that housed the university’s computer mainframe.

(El Gaucho, UC Santa Barbara)

At Moorpark College in October of 1971, black students emptied bookshelves onto the library’s floor in protest of the lack of literature grounded in their experience. These events compelled Chicanas and Chicanos to ponder what they stood for and what direct actions they themselves were to take. Hence, college and high school students networked with each other to plan programs of their own within UMAS and MEChA.

Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)—later renamed the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1972—in the adjacent county of Kern represents another geo-political consideration. From the City of Delano, he commanded strikes in the valleys of the San Joaquin (grapes), Salinas (lettuce and strawberries) and Coachella (grapes). As a humble, diminutive, swarthy man who challenged the power and privilege of the magnates of agriculture, Chavez’s outreach to colleges students reigned in and inspired the support of Chicana and Chicano true believers—many, if not most, of farmworker origins. Food, clothes, and fund drives for Cesar’s strikers were ways of participation in the farmworkers’ movement; the formation of secondary boycott demonstrations in places such as Fillmore, Santa Paula, and Oxnard was another. To benefit from his insight in relation to citrus, poultry, and strawberry strikes, Ventura County residents tapped into their personal connection with Chavez back to his 1958 Community Service Organization (CSO) campaign against the Bracero Program in the City of Oxnard. This particularly was the case in the City of Fillmore in the summer of 1970.

(Santa Paula Friends of the Farmworker Food Van, Farmworker Movement UC San Diego Online Gallery)

(Ventura County CSO 1958, Tony Del Buono, center, Carmen Yslas [a guess] center right, and Cesar Chavez far right)

On Thursday July 16, 1970, approximately five hundred citrus workers disappeared from the orchards of the F and P Growers Association in Fillmore. They demanded the announcement of the per-box pay rate before the start of each harvest day and a five cent raise. Prior to this, workers did not discover the piece rate until they received their pay—often two weeks later. As the dispute progressed, the workers formed the Santa Paula Farm Workers Committee (SPFWC) to win a $2.50 base wage, health benefits, and lower rents during the non-picking season. Due to the variation of the size of the trees and the grade and quantity of fruit in them from orchard to orchard, Warren F. Wegis, manager of the Ventura County Citrus Growers Committee, claimed it virtually impossible for the growers to determine the wage rate in advance.

Ben Aparicio, a Moorpark College student and a part-time picker in the orchards of the F and P Growers Association became a recognized leader of the strike. Aparicio on behalf of his co-workers also demanded from the growers a written redress of their grievances. This, the industry rejected. And as he spearheaded the protest, the management terminated Aparicio on May 29 for his demand to know the rate of pay at an orchard before the start of work.

Since the age of twelve, Aparicio worked alongside of his parents and four siblings in the orchards and fields of Southern California. As the strike continued Ben’s sister Manuela made leaflets that pronounced the demands for union recognition, improved homes, increased pay, as well as the statement of the wage rate at an orchard prior to the start of a day’s work. SPFWC also called for improved communication between managers and workers as many bosses in the orchards did not speak Spanish. And in addition to verbal abuse, other indignities fueled the resentment of workers. For example, the strikers claimed to be regularly cheated in their pay; citrus growers moreover refused to station port-a-sans in the orchards—particularly ignominious as work crews consisted of whole families, adults and children. As far as conditions outside the orchards, the SPFWC protested the high rents of the citrus association for substandard room and board at labor camps.

(Ben Aparicio and Cesar Chavez, left. Chavez with protesters, right. Ventura County Star Free-Press 1970)

On a Friday night, on July 17, 1970 Chavez addressed a packed room of devotees at the Guadalupe Church in the City of Santa Paula to announce the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee’s enlistment of Ventura County citrus workers as dues-paying members. In addition to these new unionists, another 350 signed cards that declared their desire to be represented by the UFWOC. Organizers achieved this after two years of work in the county. Arthur S. Gomez, the Ventura County UFWOC spokesperson, subsequently announced the intention of Chávez to address the community at Santa Paula’s La Casa Del Mexicano at 218 South 11th Street at a later date to thank the Ventura County community for its “moral and material” support during the five year grape boycott. Chavez also wished to listen to the grievances of citrus strikers in Fillmore. Although he ultimately canceled his visit due to contract negotiation in Delano, media coverage signaled his union’s intent to expand its influence in Ventura County.

In anticipation of Chavez’s next visit, the Oxnard Press-Courier noted his CSO history in the county. In fact, the specter of the tumultuous 1941 Ventura County Citrus Strike loomed in the background of the Fillmore labor dispute. A July 26 report in the Ventura County Star-Free Press fictionalized a 12 year old Chavez with a picket sign during the’41 strike even though his family had left the area over two years before. Los Angeles attorney for the Fillmore growers recalled his own work in 1941 on behalf of Charles C. Teague, president of the Ventura County Fruit Growers Exchange and founder of the brutal Associated Farmers.

At the harvest season’s peak, four thousand citrus workers, mostly men, but also women, girls, and boys, labored in the orchards of Ventura County. But this season, a good proportion struck. Gomez, also a member of Friends of the Farmworkers, informed the press that citrus pickers in Rancho Sespe and Rancho De Los Campanos, as an act of sympathy for their Fillmore brethren, left the orchards. Hence, the number of strikers grew from approximately 350 originally to 500 in the Santa Clara Valley. By July 19, 1970, an estimated number of two thousand citrus workers refused to work. To complement the walkout, a hundred and eighty people picketed the Fillmore Citrus Association at the start of each day.

(Bob Borrego, father of Diana, far right. Friends of the Farmworker, Farmworker Movement UC San Diego Online Gallery)

To raise the profile of this labor struggle, before the rise of dawn on Wednesday July 22, 1970, Chavez marshaled a procession from the F and P Growers labor camp in Fillmore to an orchard in the neighboring community of Piru to draw workers from the orchards. The march consisted of fifty men, women, and children. As they shouted, “Viva la huelga!,” the group implored pickers to join them. Overtime, the obstinacy of the capos of the citrus industry began to waver. As Chavez rallied supporters throughout Ventura County, Russel Hardison, president of the Fillmore Citrus Association, declared the intention of the grower class to extend a paid annual vacation benefit as well as the establishment of the pay rate for an orchard before the commencement of each work day. To the press, Hardison claimed that prior to the strike the grower class intended to raise the wages of workers as well as provide a vacation benefit. He went on to contest the charge that the industry charged exorbitant rents to its workers for substandard residences. In fact, the growers created 28 new residential units and remodeled 55 existing homes. The rent for newer units cost $55 a month and the older homes ranged from $30-$35. Additionally, the camp owners, they claimed, provided free water and trash removal services.

From the Aparicio home, the strikers rejected the concessions of the Fillmore Growers Association as it did not include the demands to recognize the UFWOC as their bargaining agent, improved sanitation at job sites, and the appointment of bilingual field bosses. Although citrus workers desired UFWOC representation, extant labor law (i.e, the federal National Labor Relation Act) did not apply to field or orchard workers, only shed packers. After thirteen days, the strike ended on Wednesday July 29, 1970. In exchange for paid vacation based on the hours worked during a year and the statement of wage rates at orchards before the start of work, the strikers surrendered the demand to have the UFWOC recognized as their bargaining agent. So the harvest of Valencia oranges in Fillmore, Moorpark, and Piru resumed. As usual, to save some face, the citrus industry claimed no crop losses due to the walkout. Despite this denial, the partial labor victory in Fillmore gripped the attention of the larger grower class. Consequently, toward the end of August 1970, the Matilija Growers Association in the Ojai Mountains of the county announced its decision to grant forty hours of paid vacation after the completion of nine hundred hours of orchard work in a year.

This is just one action to be featured in Chicano On!

Legacy.

In closing, the legacy of the movement of Chicanas and Chicanos continues to this day. This is by the fact that a “hard core” number of Moorpark College, Ventura, CSUN, UCLA, and UCSB alumni played a critical role in the demand for Chicana/o Studies at California State University Channel Islands. This is to say, these individuals continued the moxie of the movement of Chicanas and Chicanos so that subsequent generations would do so into the future.

C/S

fpb

CSU Northridge, Saturday August 5, 2017

Frank P. Barajas, California State University Channel Islands

Session VII: 1:30-3:00 pm. Panel 58. Ventura County’s Ethnic Histories

“Schools, Spaces, and Subjects: Chicanas and Chicanos on the Move”

Project Origins and Scope

My current project opens where Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard California, 1898-1961 (2012), my first book, finished.

From the start of the 1960s, it tracks the emergence of the crusade of Chicanas and Chicanos in Ventura County as part of a larger regional and national movement. It argues that Chicanas and Chicanos of the Sixties and Seventies in this Southern California locale expressed a politics distinct from the Mexican American Generation that came of age largely within the years of the 1940s and ’50s. Although young men and women of the Chicana and Chicano generation demanded similar reforms in education, housing, labor, and law enforcement as did many of their mentors, this set of youths expressed an exigent militancy. In this regard, I have three

potential titles that highlight the manuscript’s thesis. The first signals the work as a follow up to Curious Unions. It is Curious Insurgents: The Chicana/o Movement in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975. The other two employ poignant reflections drawn from the oral history testimonies of two Chicanas that articulate the audacity of young men and women of the period. They are Mexican Americans with Moxie: The Chicana/o Movement in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975 and Chicano On!: Mexican Americans with Moxie in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975.

In a 2013 interview, the noun moxie in the second title emerged from a pensive moment of Diana Borrego-Martinez who graduated from San Fernando Valley State College in 1972 (now CSU Northridge or CSUN) with a Chicano Studies degree. Borrego-Martinez was raised in the Ventura County community of Santa Paula. Rodolfo F. Acuña in his 2011 book The Making of Chicana/o Studies: In the Trenches of Academe described Borrego-Martinez, and approximately a dozen her peers, as “hard core” United Mexican American Students (UMAS) club members. After the conversation on the protests and arrests of the time in which she partook, she stated, “You know, we had moxie.”

(Diana Borrego-Martinez far left. Jan. 10, 1969, Los Angeles Times)

Chicano On! arose from an email’s complimentary close that followed an oral history interview with Paula Muñoz in 2016. Muñoz grew up on the Avenue in the City of Ventura and attended Ventura College before her transfer to CSUN in 1972. The phrase Chicano On! not only encapsulates the radical chic of the time but also suggests the notion that el movimiento continues to the present despite that much of the literature details a late-1970s/early-1980s requiem. At this point, my choice for the book’s title is the last as it incorporates notions of a generational becoming, fashion, and dialectical struggle. In addition, Chicano On! conveys the resolute agency of people of Mexican origin (the U.S. born as well as documented and undocumented immigrants) who crumbled dominant stereotypes of this demographic as passive, apolitical, educationally disinterested, and civically disorganized. To market the project, the subtitle also suggest the geographic and temporal mise-en-scene. Furthermore, “with moxie” speaks to how Chicanas and Chicanos of el movimiento were the activist progeny of the Mexican American Generation but with an octane indicative of the period’s larger movements of civil rights and de-colonialism. Both generations, however, worked simultaneously and informed each other while they often differed on strategy—a dynamic downplayed in the current literature.

Moreover, the historiography of the Chicana/o Movement revolves largely around the more nationally recognized, male-centric movements of Cesar Chavez’s farmworkers, Sal Castro and the student blowouts in East Los Angeles high schools, Reies Tijerina’s revanchist pursuit of New Mexican land grants, and the struggle for social and political self-determination by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and Jose Angel Gutierrez in Colorado and Texas. Such events, as in the case of the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium of August 29th 1970 against the war in Vietnam, attracted the support of fanatics from different parts of the country—even Kansas in the words of Alurista—in protean degrees and times. Consequently, this project elevates Ventura County subjects from the shadow of the metropolis of Los Angeles while it contextualizes its actions as part and parcel of such national currents.

Another facet consists of the geo-political position of Ventura County Chicana and Chicano youth. For example, to the north existed the University of California at Santa Barbara, the fount of El Plan de Santa Barbara of 1969 and schematic for the creation of Chicano Studies in and out of academe. El Plan charged students to recruit family and peers from the schools in their communities as well as afar. Then there were the institutions of San Fernando Valley State and the University of California at Los Angeles to the southeast. Both campuses recruited the underserved from Ventura County schools to the cells of activism in Los Angeles County. Conversely, UCSB attracted students such as Mayo De La Rocha of Roosevelt High School in East Los Angeles who networked with transfer students from Moorpark College and Ventura College. Many participants of the 1971 La Marcha De La Reconquista from Calexico to Sacramento, such as Yvonne de los Santos of Saticoy, were recruited by activist college students from their barrios and colonias.

(Yvonne De Los Santos, middle, image UC Santa Barbara)

(Google Maps)

Once matriculated at one of the community colleges or public universities of Southern California, Ventura County youth found themselves transformed, if not radicalized, by clubs such as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Student Union (BSU), UMAS, and later El Movimiento Estudiantíl Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). This happened as they witnessed white and black peers of SDS and the BSU, respectively, protest the war in Vietnam, racist acts on campus, and the omission of a curriculum that recognized their history. In one instance, in mid-October of 1968 Chicana and Chicano students at UCSB—many yet to be politicized—witnessed BSU students annex North Hall, the building that housed the university’s computer mainframe.

(El Gaucho, UC Santa Barbara)

At Moorpark College in October of 1971, black students emptied bookshelves onto the library’s floor in protest of the lack of literature grounded in their experience. These events compelled Chicanas and Chicanos to ponder what they stood for and what direct actions they themselves were to take. Hence, college and high school students networked with each other to plan programs of their own within UMAS and MEChA.

Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)—later renamed the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1972—in the adjacent county of Kern represents another geo-political consideration. From the City of Delano, he commanded strikes in the valleys of the San Joaquin (grapes), Salinas (lettuce and strawberries) and Coachella (grapes). As a humble, diminutive, swarthy man who challenged the power and privilege of the magnates of agriculture, Chavez’s outreach to colleges students reigned in and inspired the support of Chicana and Chicano true believers—many, if not most, of farmworker origins. Food, clothes, and fund drives for Cesar’s strikers were ways of participation in the farmworkers’ movement; the formation of secondary boycott demonstrations in places such as Fillmore, Santa Paula, and Oxnard was another. To benefit from his insight in relation to citrus, poultry, and strawberry strikes, Ventura County residents tapped into their personal connection with Chavez back to his 1958 Community Service Organization (CSO) campaign against the Bracero Program in the City of Oxnard. This particularly was the case in the City of Fillmore in the summer of 1970.

(Santa Paula Friends of the Farmworker Food Van, Farmworker Movement UC San Diego Online Gallery)

(Ventura County CSO 1958, Tony Del Buono, center, Carmen Yslas [a guess] center right, and Cesar Chavez far right)

On Thursday July 16, 1970, approximately five hundred citrus workers disappeared from the orchards of the F and P Growers Association in Fillmore. They demanded the announcement of the per-box pay rate before the start of each harvest day and a five cent raise. Prior to this, workers did not discover the piece rate until they received their pay—often two weeks later. As the dispute progressed, the workers formed the Santa Paula Farm Workers Committee (SPFWC) to win a $2.50 base wage, health benefits, and lower rents during the non-picking season. Due to the variation of the size of the trees and the grade and quantity of fruit in them from orchard to orchard, Warren F. Wegis, manager of the Ventura County Citrus Growers Committee, claimed it virtually impossible for the growers to determine the wage rate in advance.

Ben Aparicio, a Moorpark College student and a part-time picker in the orchards of the F and P Growers Association became a recognized leader of the strike. Aparicio on behalf of his co-workers also demanded from the growers a written redress of their grievances. This, the industry rejected. And as he spearheaded the protest, the management terminated Aparicio on May 29 for his demand to know the rate of pay at an orchard before the start of work.

Since the age of twelve, Aparicio worked alongside of his parents and four siblings in the orchards and fields of Southern California. As the strike continued Ben’s sister Manuela made leaflets that pronounced the demands for union recognition, improved homes, increased pay, as well as the statement of the wage rate at an orchard prior to the start of a day’s work. SPFWC also called for improved communication between managers and workers as many bosses in the orchards did not speak Spanish. And in addition to verbal abuse, other indignities fueled the resentment of workers. For example, the strikers claimed to be regularly cheated in their pay; citrus growers moreover refused to station port-a-sans in the orchards—particularly ignominious as work crews consisted of whole families, adults and children. As far as conditions outside the orchards, the SPFWC protested the high rents of the citrus association for substandard room and board at labor camps.

(Ben Aparicio and Cesar Chavez, left. Chavez with protesters, right. Ventura County Star Free-Press 1970)

On a Friday night, on July 17, 1970 Chavez addressed a packed room of devotees at the Guadalupe Church in the City of Santa Paula to announce the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee’s enlistment of Ventura County citrus workers as dues-paying members. In addition to these new unionists, another 350 signed cards that declared their desire to be represented by the UFWOC. Organizers achieved this after two years of work in the county. Arthur S. Gomez, the Ventura County UFWOC spokesperson, subsequently announced the intention of Chávez to address the community at Santa Paula’s La Casa Del Mexicano at 218 South 11th Street at a later date to thank the Ventura County community for its “moral and material” support during the five year grape boycott. Chavez also wished to listen to the grievances of citrus strikers in Fillmore. Although he ultimately canceled his visit due to contract negotiation in Delano, media coverage signaled his union’s intent to expand its influence in Ventura County.

In anticipation of Chavez’s next visit, the Oxnard Press-Courier noted his CSO history in the county. In fact, the specter of the tumultuous 1941 Ventura County Citrus Strike loomed in the background of the Fillmore labor dispute. A July 26 report in the Ventura County Star-Free Press fictionalized a 12 year old Chavez with a picket sign during the’41 strike even though his family had left the area over two years before. Los Angeles attorney for the Fillmore growers recalled his own work in 1941 on behalf of Charles C. Teague, president of the Ventura County Fruit Growers Exchange and founder of the brutal Associated Farmers.

At the harvest season’s peak, four thousand citrus workers, mostly men, but also women, girls, and boys, labored in the orchards of Ventura County. But this season, a good proportion struck. Gomez, also a member of Friends of the Farmworkers, informed the press that citrus pickers in Rancho Sespe and Rancho De Los Campanos, as an act of sympathy for their Fillmore brethren, left the orchards. Hence, the number of strikers grew from approximately 350 originally to 500 in the Santa Clara Valley. By July 19, 1970, an estimated number of two thousand citrus workers refused to work. To complement the walkout, a hundred and eighty people picketed the Fillmore Citrus Association at the start of each day.

(Bob Borrego, father of Diana, far right. Friends of the Farmworker, Farmworker Movement UC San Diego Online Gallery)

To raise the profile of this labor struggle, before the rise of dawn on Wednesday July 22, 1970, Chavez marshaled a procession from the F and P Growers labor camp in Fillmore to an orchard in the neighboring community of Piru to draw workers from the orchards. The march consisted of fifty men, women, and children. As they shouted, “Viva la huelga!,” the group implored pickers to join them. Overtime, the obstinacy of the capos of the citrus industry began to waver. As Chavez rallied supporters throughout Ventura County, Russel Hardison, president of the Fillmore Citrus Association, declared the intention of the grower class to extend a paid annual vacation benefit as well as the establishment of the pay rate for an orchard before the commencement of each work day. To the press, Hardison claimed that prior to the strike the grower class intended to raise the wages of workers as well as provide a vacation benefit. He went on to contest the charge that the industry charged exorbitant rents to its workers for substandard residences. In fact, the growers created 28 new residential units and remodeled 55 existing homes. The rent for newer units cost $55 a month and the older homes ranged from $30-$35. Additionally, the camp owners, they claimed, provided free water and trash removal services.

From the Aparicio home, the strikers rejected the concessions of the Fillmore Growers Association as it did not include the demands to recognize the UFWOC as their bargaining agent, improved sanitation at job sites, and the appointment of bilingual field bosses. Although citrus workers desired UFWOC representation, extant labor law (i.e, the federal National Labor Relation Act) did not apply to field or orchard workers, only shed packers. After thirteen days, the strike ended on Wednesday July 29, 1970. In exchange for paid vacation based on the hours worked during a year and the statement of wage rates at orchards before the start of work, the strikers surrendered the demand to have the UFWOC recognized as their bargaining agent. So the harvest of Valencia oranges in Fillmore, Moorpark, and Piru resumed. As usual, to save some face, the citrus industry claimed no crop losses due to the walkout. Despite this denial, the partial labor victory in Fillmore gripped the attention of the larger grower class. Consequently, toward the end of August 1970, the Matilija Growers Association in the Ojai Mountains of the county announced its decision to grant forty hours of paid vacation after the completion of nine hundred hours of orchard work in a year.

This is just one action to be featured in Chicano On!

Legacy.

In closing, the legacy of the movement of Chicanas and Chicanos continues to this day. This is by the fact that a “hard core” number of Moorpark College, Ventura, CSUN, UCLA, and UCSB alumni played a critical role in the demand for Chicana/o Studies at California State University Channel Islands. This is to say, these individuals continued the moxie of the movement of Chicanas and Chicanos so that subsequent generations would do so into the future.

C/S

fpb

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Twice In One Week: An Educational Barrier of the Past and Present

Twice in one week! I listened to two related stories of triumph; I wish, however, that this familiar narrative would die. I have studied the past, been admonished by my parents at the dinner table as a youth, and frustrated by the not uncommon accounts of students and colleagues how high school counselors continue to steer away Mexican-origin youth from college-prep courses.

At a May 3rd Future Leaders of America forum at Cesar Chavez Elementary, students of the Oxnard Union High School District delivered data and testimonies on the achievement gap in their respective campuses in comparison to schools in Ventura County’s more affluent communities.

Actually, A-G admission requirements for the California State University and University of California framed the discussion. A FLA study indicates while Hispanics made up 75% of the students in the OUHSD in 2014, only 22% of graduating seniors from this demographic completed coursework to attend a CSU or UC.

In addition to the factors of family income and race that defines the character of college admissions, the discretion of one high school counselor in particular echoed the racist expectations of 20th century educators who assumed that parents and students of Mexican-origin did not value education.

To combat this persistent lie, each FLA presenter, some 15 talented high school students in all, declared, “We value education.” One in particular shared the story how he made repeated pleas to his counselor to be enrolled in honors courses only to be told that not a single section had room for him. Determined to prepare himself for college, he approached the teachers of such classes to ask if open seats existed. All replied yes.

The counselor, however, did not budge. Even more resolute, though, this student made an appointment with the campus principal to meet with him and his parents. Only then was he allowed to take the courses he wanted. As a result of his brio, he will graduate this year #1 in his class and attend the University of California at Berkeley in the fall.

“Halleluiah!” I said to myself as I held back from standing up in the audience to shout, “That counselor must be fired!”

Afterward, OUHSD Superintendent Dr. Penelope DeLeon provided another silver lining. She announced the district’s increase in Advance Placement course enrollments by 1,069 college bound students. To replace unsatisfactory grades, students will also have the opportunity to retake A-G classes in the summer. Added to this, the district will cover the registration cost of all its students to take the college PSAT and SAT.

Two days later, I participated in the presidential investiture ceremony of my new boss, Dr. Erika D. Beck, at CSU Channel Islands. After the congratulatory speeches of colleagues, friends, and family, Dr. Beck professed the power of a higher education to transform lives. To prove this, she exampled the story of Judge Michele M. Castillo, appointed to the Ventura County Superior Court in 2016.

Among several challenges in her family while growing up, Judge Castillo’s father battled alcoholism. To shield herself from the discord in a household that accompanies addiction, the isolation of study was Michele’s refuge and going away to a university her escape plan. Similar to the experience of the FLA student, however, her Buena High School counselor discouraged her, too, from an AP load of classes. For the young Michele, this counselor created a schedule in home economics. No college needed for her.

Despite this lack of encouragement, she enrolled in the classes she demanded and was accepted by UCLA, UC Davis, USC, and Stanford. She became a Bruin, graduated, and went on to earn a law degree from Thomas Jefferson Law School in San Diego. After a 13 year tenure as a public defender, Judge Castillo now serves as a role model of the possible in her community while ensuring equal justice for all.

Although stories of the FLA student and Judge Castillo are of perseverance, they highlight an exceptionalism. But how many persons—particularly of Mexican origin and others from the historically underserved—have not enjoyed the improved life chances that comes with a higher education due to the low expectations of educators? Too many. Educational data tells us this.

So what’s the answer? Increased state funding for K-14 public schools, the CSU, and UC so an army of culturally competent and sensitive counselors can encourage all students to pursue a higher education, especially for those who embrace this dream.

As President Beck referenced a 2015 Public Policy Institute of California study, this is an imperative as the state’s economy will face a shortfall of 1.1 million employees with baccalaureate degrees by 2030. This is while nearly 55% of students in the state’s educational pipeline consist of Hispanic youth. As a federally recognized Hispanic Serving Institution, over fifty percent of CSU Channel Islands’ student body alone consist of people, largely, of Mexican origin.

To meet the state’s demand for a highly skilled workforce, the people of California must force elected state and federal representatives such as President Donald Trump; Governor Jerry Brown; Senators Diane Feinstein and Kamala Harris; House of Representative members Julia Brownley and Salud Carbajal; and state senators Hannah Beth Jackson and Henry Stern; and assemblymembers Jacqui Irwin and Monique Limon; and others to fully fund public education beyond the levels of the Great Recession of 2007.

For this to happen, call them (and other elected officials) to make this demand. Their contact information can be found at votesmart.org.

C/S

fpb

At a May 3rd Future Leaders of America forum at Cesar Chavez Elementary, students of the Oxnard Union High School District delivered data and testimonies on the achievement gap in their respective campuses in comparison to schools in Ventura County’s more affluent communities.

Actually, A-G admission requirements for the California State University and University of California framed the discussion. A FLA study indicates while Hispanics made up 75% of the students in the OUHSD in 2014, only 22% of graduating seniors from this demographic completed coursework to attend a CSU or UC.

In addition to the factors of family income and race that defines the character of college admissions, the discretion of one high school counselor in particular echoed the racist expectations of 20th century educators who assumed that parents and students of Mexican-origin did not value education.

To combat this persistent lie, each FLA presenter, some 15 talented high school students in all, declared, “We value education.” One in particular shared the story how he made repeated pleas to his counselor to be enrolled in honors courses only to be told that not a single section had room for him. Determined to prepare himself for college, he approached the teachers of such classes to ask if open seats existed. All replied yes.

The counselor, however, did not budge. Even more resolute, though, this student made an appointment with the campus principal to meet with him and his parents. Only then was he allowed to take the courses he wanted. As a result of his brio, he will graduate this year #1 in his class and attend the University of California at Berkeley in the fall.

“Halleluiah!” I said to myself as I held back from standing up in the audience to shout, “That counselor must be fired!”

Afterward, OUHSD Superintendent Dr. Penelope DeLeon provided another silver lining. She announced the district’s increase in Advance Placement course enrollments by 1,069 college bound students. To replace unsatisfactory grades, students will also have the opportunity to retake A-G classes in the summer. Added to this, the district will cover the registration cost of all its students to take the college PSAT and SAT.

Two days later, I participated in the presidential investiture ceremony of my new boss, Dr. Erika D. Beck, at CSU Channel Islands. After the congratulatory speeches of colleagues, friends, and family, Dr. Beck professed the power of a higher education to transform lives. To prove this, she exampled the story of Judge Michele M. Castillo, appointed to the Ventura County Superior Court in 2016.

Among several challenges in her family while growing up, Judge Castillo’s father battled alcoholism. To shield herself from the discord in a household that accompanies addiction, the isolation of study was Michele’s refuge and going away to a university her escape plan. Similar to the experience of the FLA student, however, her Buena High School counselor discouraged her, too, from an AP load of classes. For the young Michele, this counselor created a schedule in home economics. No college needed for her.

Despite this lack of encouragement, she enrolled in the classes she demanded and was accepted by UCLA, UC Davis, USC, and Stanford. She became a Bruin, graduated, and went on to earn a law degree from Thomas Jefferson Law School in San Diego. After a 13 year tenure as a public defender, Judge Castillo now serves as a role model of the possible in her community while ensuring equal justice for all.

Although stories of the FLA student and Judge Castillo are of perseverance, they highlight an exceptionalism. But how many persons—particularly of Mexican origin and others from the historically underserved—have not enjoyed the improved life chances that comes with a higher education due to the low expectations of educators? Too many. Educational data tells us this.

So what’s the answer? Increased state funding for K-14 public schools, the CSU, and UC so an army of culturally competent and sensitive counselors can encourage all students to pursue a higher education, especially for those who embrace this dream.

As President Beck referenced a 2015 Public Policy Institute of California study, this is an imperative as the state’s economy will face a shortfall of 1.1 million employees with baccalaureate degrees by 2030. This is while nearly 55% of students in the state’s educational pipeline consist of Hispanic youth. As a federally recognized Hispanic Serving Institution, over fifty percent of CSU Channel Islands’ student body alone consist of people, largely, of Mexican origin.

To meet the state’s demand for a highly skilled workforce, the people of California must force elected state and federal representatives such as President Donald Trump; Governor Jerry Brown; Senators Diane Feinstein and Kamala Harris; House of Representative members Julia Brownley and Salud Carbajal; and state senators Hannah Beth Jackson and Henry Stern; and assemblymembers Jacqui Irwin and Monique Limon; and others to fully fund public education beyond the levels of the Great Recession of 2007.

For this to happen, call them (and other elected officials) to make this demand. Their contact information can be found at votesmart.org.

C/S

fpb

Friday, April 21, 2017

Talking Points to Veterans on Writing

Below are talking points I delivered to military veterans of California State University Channel Islands.

Follow directions.

Read, read, and read more. Non-fiction and fiction, short stories, op-eds, magazines (The New Yorker is a must). Charles Dickens, Harper Lee, Edgar Allen Poe (gloomy stories), Gloria Anzaldua, Rodolfo Anaya, George Orwell, Mary Twain, Willa Cather, Richard Wright.

As you read:

• Study how stories are constructed from start to finish. How do paragraphs vary? How are punctuation marks used and manipulated, especially the comma.

• Read books on writing. E.B. White's _Elements of Style_ is a good start. I loved Stephen King’s book on writing titled, _On Writing_. _The Dead Zone_ was also one of the first books I read cover to cover and scared me through the whole process.

• Increase your vocabulary and notice how ideas are conveyed, and even toyed with, by words.

•To start your writing bullet points are fine. Each bullet point can be a page or paragraph of your main idea (thesis, argument). As you move forward, tease out your ideas and then eliminate the bullets.

Writing is hard. Take if from people like Franz Kafka and Emily Dickinson who described it as painful (at least Kafka did) and wrote for themselves and not others. Kafka almost destroyed all his writings at one point. And Dickinson stashed away many of hers, only to be discovered recently--I read this in The New Yorker a few months back. I love her poem _Because I Could Not Stop for Death_. This is a reflection of my saturnine side, hence Poe.

Allow yourself the freedom to make mistakes. But at the same time be careful in what you want to communicate by way the written word. Don’t be afraid of what others might think. The hell with those who will be offended, even your friends. So write boldly, honestly, and clearly. Be vulnerable. This is what makes writing interesting.

For term papers, write drafts (more than 2-3, at least).

The outline. When do you create one? Before? As you go? Both?

Follow carefully the directions of professor’s as stated in their instruction sheets. Most spend a chingo of time creating them. It is wonder how many students ignore my instructions and as a result fall short of assignment expectations.

Furthermore, as you move forward in the development of your finished paper,:

*meet the minimum pages of writing. Keep in mind that a minimum page of required writing could and most likely will translate into, at best, a minimum passing score.

*State clearly your thesis/main Idea/theoretical framework/argument of your project. This may/will change as you develop your paper.

*One way to achieve immortality is to leave a body of writing. You never know where it may end up.

Proof read your writing, especially if you’re are a lousy keyboarder as I am. For a good example of this, see above.

In conclusion, avoid starting your writing with hackneyed phrases, especially in regards to the weather.

C/S

fpb

Follow directions.

Read, read, and read more. Non-fiction and fiction, short stories, op-eds, magazines (The New Yorker is a must). Charles Dickens, Harper Lee, Edgar Allen Poe (gloomy stories), Gloria Anzaldua, Rodolfo Anaya, George Orwell, Mary Twain, Willa Cather, Richard Wright.

As you read:

• Study how stories are constructed from start to finish. How do paragraphs vary? How are punctuation marks used and manipulated, especially the comma.

• Read books on writing. E.B. White's _Elements of Style_ is a good start. I loved Stephen King’s book on writing titled, _On Writing_. _The Dead Zone_ was also one of the first books I read cover to cover and scared me through the whole process.

• Increase your vocabulary and notice how ideas are conveyed, and even toyed with, by words.

•To start your writing bullet points are fine. Each bullet point can be a page or paragraph of your main idea (thesis, argument). As you move forward, tease out your ideas and then eliminate the bullets.

Writing is hard. Take if from people like Franz Kafka and Emily Dickinson who described it as painful (at least Kafka did) and wrote for themselves and not others. Kafka almost destroyed all his writings at one point. And Dickinson stashed away many of hers, only to be discovered recently--I read this in The New Yorker a few months back. I love her poem _Because I Could Not Stop for Death_. This is a reflection of my saturnine side, hence Poe.

Allow yourself the freedom to make mistakes. But at the same time be careful in what you want to communicate by way the written word. Don’t be afraid of what others might think. The hell with those who will be offended, even your friends. So write boldly, honestly, and clearly. Be vulnerable. This is what makes writing interesting.

For term papers, write drafts (more than 2-3, at least).

The outline. When do you create one? Before? As you go? Both?

Follow carefully the directions of professor’s as stated in their instruction sheets. Most spend a chingo of time creating them. It is wonder how many students ignore my instructions and as a result fall short of assignment expectations.

Furthermore, as you move forward in the development of your finished paper,:

*meet the minimum pages of writing. Keep in mind that a minimum page of required writing could and most likely will translate into, at best, a minimum passing score.

*State clearly your thesis/main Idea/theoretical framework/argument of your project. This may/will change as you develop your paper.

*One way to achieve immortality is to leave a body of writing. You never know where it may end up.

Proof read your writing, especially if you’re are a lousy keyboarder as I am. For a good example of this, see above.

In conclusion, avoid starting your writing with hackneyed phrases, especially in regards to the weather.

C/S

fpb

Sunday, April 9, 2017

No Puente Program in VC: What's Up With That?

Since returning to Ventura County in 2001, I continue to be baffled why the Ventura County Community College District fails (as well as area high school distritcts) to have a Puente Program. It has proven to significantly enhance the transfer of students to four year colleges and university. Cypress College (where I previously worked for 9 years) fought for it when I was there--thanks to the intrepid leadership of Dr. Enriqueta Ramos and MEChA. Today, Cypress College's Puente Program is strong and continues to have outstanding rates of transfer, especially when compared to the overall dismal rate of transfer in the California Community College system.

Even Puente alumni in VC don't champion this cause. What's up with that?

C/S

fpb

Even Puente alumni in VC don't champion this cause. What's up with that?

C/S

fpb

Monday, January 2, 2017

Trucha (Look Out): You’re Being Watched—Too!

According to Turning Point USA, I am one of two hundred professors, “who discriminate against conservative students and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.” Consequently, by way of its dubious Professor Watchlist, TPUSA contends that its purpose is to inform alumni, parents, and students of, “specific incidents and names of professors that advance a radical agenda in lecture halls.”

But TPUSA’s insidious real aim is to intimidate and single out educators to complement President-elect Donald Trump’s rising number of like registries for their faith, in the case of Muslims, journalists, and employees within the State Department and Department of Energy who advocate, respectively, for the rights of women and the LGBT community as well as the health of our planet.

The creation of lists that target intellectuals and educators echoes loudly in history. One reverberation is described by historian Karl Dietrich Bracher in his classic work The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure and Effects of National Socialism (1970). Another is in the movie the Killing Fields (1984) based on New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg’s coverage of Cambodia’s civil war of the 1970s.

In the former, Hitler—who was no socialist but used the label to attract the left behind working-class of Germany—and his Nazis killed targeted professors, intellectuals, and bureaucrats that he believed threatened his regime. For the latter, a scene demonstrates how Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge tricked imprisoned teachers and other professionals into identifying themselves only to be executed by suffocation.

Lesson: thinkers threaten totalitarian rulers. So members of the intelligentsia must be branded and dealt with accordingly.

Charlie Kirk, the 25 year old Founder and Executive Director of TPUSA, culled my name for identification from a Campus Reform post written by Anthony Gockowski who utilized a cooked version of my extra-credit assignment of the spring 2016 semester for a US History survey course. Gockowski also misrepresented its guidelines.

The exercise—one of several such opportunities I offer to promote civic engagement, critical thinking, and effective writing—encouraged students to contact their assembly and senate representatives in the California legislature to express how tuition of the California State University affected them and their families.

From this experience, I envisioned first-generation college students learning to format a business letter, discover (if they did not already know) who their elected representatives in the legislature were, and understand how to petition their government for a redress of grievances, if they had any.

Contrary to Campus Reform’s mendacious blog post, my instructions did not mandate the content of student letters. As context, however, I did provide essays I wrote on the subject that argued for a fully subsidized system of public higher education.

But in the Age of Trump and his gaslighting propaganda (i.e., a program of deception and deceit) and that of his surrogates, what does truth and accuracy have to do with anything?

Despite the disingenuous spotlight of TPUSA and Campus Reform, I again offered the business letter to elected official exercise as an extra-credit option this past fall semester. Like in previous semesters, the letters articulated the economic and psychological stress that high tuition cost of the CSU places on them and their family. To stay in enrolled in college, students work longer hours, incur unforgiveable debt in the tens of thousands of dollars, and their parents and grandparents burn through college funds, often in the first year, to provide their children with a higher education that my generation enjoyed at a fraction of the cost.

And this is just for one person in a family who dares to pursue a university degree.

As a graduate of the CSU in the 1980s, I cannot imagine starting my career or continuing onto graduate school as a twenty-something year old $20,000, $30,000 or more in student loan debt. With this in mind, I wonder how many willing and able young people have decided to forego a college education altogether as a result.

But that is the goal of right-wing groups such as TPSU, Campus Reform, and their millionaire benefactors that include people and groups of the likes of investor and Donald Trump supporter Foster Freiss, in the case of TPSU, and Leadership Institute founder and also Trump supporter Morton C. Blackwell.

Like the idea of universal health care, this gaggle of Ayn Rand objectivist adherents wish to promote a market economy where oligarchs further enrich themselves in a fully privatized system of education off the backs of working-class students and parents saddled with intergenerational debt.

An educated citizenry that speaks to power, is civically engaged, and draws lessons from the past would expose the fictions that define the reality of such right-wing groups. In fact, in the late 1960s it was their demigod Ronald Reagan who proposed higher tuition costs and education budget cuts as California governor to stem student activism.

Moreover, such political conservatives dread the historical reference of a public higher education in California once being virtually free prior to the 1980s.

So what’s the solution? Like the sponsors of TPUSA and LI, people of financial means that believe that an affordable public higher education is vital to the production of an engaged and informed citizenry need to develop, fund, and support the work of the counterparts of Kirk and Gockowski. Otherwise, publicly funded systems of education, health, and retirement will be completely abolished. Gross profit margins will then be the sole priority of private sector run social services over the needs of people.

Meanwhile, I will continue my letter writing extra-credit assignment as well have my US History students study primary documents from the following list that consist: James Madison’s Federalist #10, Henry David Thoreau’s On Civil Disobedience, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, Andrew Carnegie’s essay on Wealth, Emma Goldman and John Most’s Anarchy Defended by Anarchists, Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, and the Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Platform and Program.

Such informed dissent of the past is our only hope for a more just future.

C/S

fpb

Amigos805 LatinoLA History News Network RawStory

But TPUSA’s insidious real aim is to intimidate and single out educators to complement President-elect Donald Trump’s rising number of like registries for their faith, in the case of Muslims, journalists, and employees within the State Department and Department of Energy who advocate, respectively, for the rights of women and the LGBT community as well as the health of our planet.

The creation of lists that target intellectuals and educators echoes loudly in history. One reverberation is described by historian Karl Dietrich Bracher in his classic work The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure and Effects of National Socialism (1970). Another is in the movie the Killing Fields (1984) based on New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg’s coverage of Cambodia’s civil war of the 1970s.

In the former, Hitler—who was no socialist but used the label to attract the left behind working-class of Germany—and his Nazis killed targeted professors, intellectuals, and bureaucrats that he believed threatened his regime. For the latter, a scene demonstrates how Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge tricked imprisoned teachers and other professionals into identifying themselves only to be executed by suffocation.

Lesson: thinkers threaten totalitarian rulers. So members of the intelligentsia must be branded and dealt with accordingly.

Charlie Kirk, the 25 year old Founder and Executive Director of TPUSA, culled my name for identification from a Campus Reform post written by Anthony Gockowski who utilized a cooked version of my extra-credit assignment of the spring 2016 semester for a US History survey course. Gockowski also misrepresented its guidelines.

The exercise—one of several such opportunities I offer to promote civic engagement, critical thinking, and effective writing—encouraged students to contact their assembly and senate representatives in the California legislature to express how tuition of the California State University affected them and their families.

From this experience, I envisioned first-generation college students learning to format a business letter, discover (if they did not already know) who their elected representatives in the legislature were, and understand how to petition their government for a redress of grievances, if they had any.

Contrary to Campus Reform’s mendacious blog post, my instructions did not mandate the content of student letters. As context, however, I did provide essays I wrote on the subject that argued for a fully subsidized system of public higher education.

But in the Age of Trump and his gaslighting propaganda (i.e., a program of deception and deceit) and that of his surrogates, what does truth and accuracy have to do with anything?

Despite the disingenuous spotlight of TPUSA and Campus Reform, I again offered the business letter to elected official exercise as an extra-credit option this past fall semester. Like in previous semesters, the letters articulated the economic and psychological stress that high tuition cost of the CSU places on them and their family. To stay in enrolled in college, students work longer hours, incur unforgiveable debt in the tens of thousands of dollars, and their parents and grandparents burn through college funds, often in the first year, to provide their children with a higher education that my generation enjoyed at a fraction of the cost.

And this is just for one person in a family who dares to pursue a university degree.

As a graduate of the CSU in the 1980s, I cannot imagine starting my career or continuing onto graduate school as a twenty-something year old $20,000, $30,000 or more in student loan debt. With this in mind, I wonder how many willing and able young people have decided to forego a college education altogether as a result.

But that is the goal of right-wing groups such as TPSU, Campus Reform, and their millionaire benefactors that include people and groups of the likes of investor and Donald Trump supporter Foster Freiss, in the case of TPSU, and Leadership Institute founder and also Trump supporter Morton C. Blackwell.

Like the idea of universal health care, this gaggle of Ayn Rand objectivist adherents wish to promote a market economy where oligarchs further enrich themselves in a fully privatized system of education off the backs of working-class students and parents saddled with intergenerational debt.

An educated citizenry that speaks to power, is civically engaged, and draws lessons from the past would expose the fictions that define the reality of such right-wing groups. In fact, in the late 1960s it was their demigod Ronald Reagan who proposed higher tuition costs and education budget cuts as California governor to stem student activism.

Moreover, such political conservatives dread the historical reference of a public higher education in California once being virtually free prior to the 1980s.

So what’s the solution? Like the sponsors of TPUSA and LI, people of financial means that believe that an affordable public higher education is vital to the production of an engaged and informed citizenry need to develop, fund, and support the work of the counterparts of Kirk and Gockowski. Otherwise, publicly funded systems of education, health, and retirement will be completely abolished. Gross profit margins will then be the sole priority of private sector run social services over the needs of people.

Meanwhile, I will continue my letter writing extra-credit assignment as well have my US History students study primary documents from the following list that consist: James Madison’s Federalist #10, Henry David Thoreau’s On Civil Disobedience, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, Andrew Carnegie’s essay on Wealth, Emma Goldman and John Most’s Anarchy Defended by Anarchists, Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, and the Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Platform and Program.

Such informed dissent of the past is our only hope for a more just future.

C/S

fpb

Amigos805 LatinoLA History News Network RawStory

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)