Pacific Coast Branch-American Historical Association

CSU Northridge, Saturday August 5, 2017

Frank P. Barajas, California State University Channel Islands

Session VII: 1:30-3:00 pm. Panel 58. Ventura County’s Ethnic Histories

“Schools, Spaces, and Subjects: Chicanas and Chicanos on the Move”

Project Origins and Scope

My current project opens where Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard California, 1898-1961 (2012), my first book, finished.

From the start of the 1960s, it tracks the emergence of the crusade of Chicanas and Chicanos in Ventura County as part of a larger regional and national movement. It argues that Chicanas and Chicanos of the Sixties and Seventies in this Southern California locale expressed a politics distinct from the Mexican American Generation that came of age largely within the years of the 1940s and ’50s. Although young men and women of the Chicana and Chicano generation demanded similar reforms in education, housing, labor, and law enforcement as did many of their mentors, this set of youths expressed an exigent militancy. In this regard, I have three

potential titles that highlight the manuscript’s thesis. The first signals the work as a follow up to Curious Unions. It is Curious Insurgents: The Chicana/o Movement in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975. The other two employ poignant reflections drawn from the oral history testimonies of two Chicanas that articulate the audacity of young men and women of the period. They are Mexican Americans with Moxie: The Chicana/o Movement in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975 and Chicano On!: Mexican Americans with Moxie in Ventura County, California, 1961-1975.

In a 2013 interview, the noun moxie in the second title emerged from a pensive moment of Diana Borrego-Martinez who graduated from San Fernando Valley State College in 1972 (now CSU Northridge or CSUN) with a Chicano Studies degree. Borrego-Martinez was raised in the Ventura County community of Santa Paula. Rodolfo F. Acuña in his 2011 book The Making of Chicana/o Studies: In the Trenches of Academe described Borrego-Martinez, and approximately a dozen her peers, as “hard core” United Mexican American Students (UMAS) club members. After the conversation on the protests and arrests of the time in which she partook, she stated, “You know, we had moxie.”

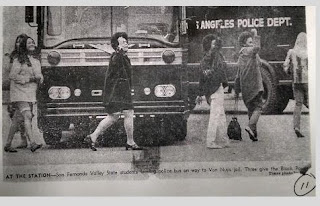

(Diana Borrego-Martinez far left. Jan. 10, 1969, Los Angeles Times)

Chicano On! arose from an email’s complimentary close that followed an oral history interview with Paula Muñoz in 2016. Muñoz grew up on the Avenue in the City of Ventura and attended Ventura College before her transfer to CSUN in 1972. The phrase Chicano On! not only encapsulates the radical chic of the time but also suggests the notion that el movimiento continues to the present despite that much of the literature details a late-1970s/early-1980s requiem. At this point, my choice for the book’s title is the last as it incorporates notions of a generational becoming, fashion, and dialectical struggle. In addition, Chicano On! conveys the resolute agency of people of Mexican origin (the U.S. born as well as documented and undocumented immigrants) who crumbled dominant stereotypes of this demographic as passive, apolitical, educationally disinterested, and civically disorganized. To market the project, the subtitle also suggest the geographic and temporal mise-en-scene. Furthermore, “with moxie” speaks to how Chicanas and Chicanos of el movimiento were the activist progeny of the Mexican American Generation but with an octane indicative of the period’s larger movements of civil rights and de-colonialism. Both generations, however, worked simultaneously and informed each other while they often differed on strategy—a dynamic downplayed in the current literature.

Moreover, the historiography of the Chicana/o Movement revolves largely around the more nationally recognized, male-centric movements of Cesar Chavez’s farmworkers, Sal Castro and the student blowouts in East Los Angeles high schools, Reies Tijerina’s revanchist pursuit of New Mexican land grants, and the struggle for social and political self-determination by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and Jose Angel Gutierrez in Colorado and Texas. Such events, as in the case of the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium of August 29th 1970 against the war in Vietnam, attracted the support of fanatics from different parts of the country—even Kansas in the words of Alurista—in protean degrees and times. Consequently, this project elevates Ventura County subjects from the shadow of the metropolis of Los Angeles while it contextualizes its actions as part and parcel of such national currents.

Another facet consists of the geo-political position of Ventura County Chicana and Chicano youth. For example, to the north existed the University of California at Santa Barbara, the fount of El Plan de Santa Barbara of 1969 and schematic for the creation of Chicano Studies in and out of academe. El Plan charged students to recruit family and peers from the schools in their communities as well as afar. Then there were the institutions of San Fernando Valley State and the University of California at Los Angeles to the southeast. Both campuses recruited the underserved from Ventura County schools to the cells of activism in Los Angeles County. Conversely, UCSB attracted students such as Mayo De La Rocha of Roosevelt High School in East Los Angeles who networked with transfer students from Moorpark College and Ventura College. Many participants of the 1971 La Marcha De La Reconquista from Calexico to Sacramento, such as Yvonne de los Santos of Saticoy, were recruited by activist college students from their barrios and colonias.

(Yvonne De Los Santos, middle, image UC Santa Barbara)

(Google Maps)

Once matriculated at one of the community colleges or public universities of Southern California, Ventura County youth found themselves transformed, if not radicalized, by clubs such as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Student Union (BSU), UMAS, and later El Movimiento Estudiantíl Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). This happened as they witnessed white and black peers of SDS and the BSU, respectively, protest the war in Vietnam, racist acts on campus, and the omission of a curriculum that recognized their history. In one instance, in mid-October of 1968 Chicana and Chicano students at UCSB—many yet to be politicized—witnessed BSU students annex North Hall, the building that housed the university’s computer mainframe.

(El Gaucho, UC Santa Barbara)

At Moorpark College in October of 1971, black students emptied bookshelves onto the library’s floor in protest of the lack of literature grounded in their experience. These events compelled Chicanas and Chicanos to ponder what they stood for and what direct actions they themselves were to take. Hence, college and high school students networked with each other to plan programs of their own within UMAS and MEChA.

Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)—later renamed the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1972—in the adjacent county of Kern represents another geo-political consideration. From the City of Delano, he commanded strikes in the valleys of the San Joaquin (grapes), Salinas (lettuce and strawberries) and Coachella (grapes). As a humble, diminutive, swarthy man who challenged the power and privilege of the magnates of agriculture, Chavez’s outreach to colleges students reigned in and inspired the support of Chicana and Chicano true believers—many, if not most, of farmworker origins. Food, clothes, and fund drives for Cesar’s strikers were ways of participation in the farmworkers’ movement; the formation of secondary boycott demonstrations in places such as Fillmore, Santa Paula, and Oxnard was another. To benefit from his insight in relation to citrus, poultry, and strawberry strikes, Ventura County residents tapped into their personal connection with Chavez back to his 1958 Community Service Organization (CSO) campaign against the Bracero Program in the City of Oxnard. This particularly was the case in the City of Fillmore in the summer of 1970.

(Santa Paula Friends of the Farmworker Food Van, Farmworker Movement UC San Diego Online Gallery)

(Ventura County CSO 1958, Tony Del Buono, center, Carmen Yslas [a guess] center right, and Cesar Chavez far right)

On Thursday July 16, 1970, approximately five hundred citrus workers disappeared from the orchards of the F and P Growers Association in Fillmore. They demanded the announcement of the per-box pay rate before the start of each harvest day and a five cent raise. Prior to this, workers did not discover the piece rate until they received their pay—often two weeks later. As the dispute progressed, the workers formed the Santa Paula Farm Workers Committee (SPFWC) to win a $2.50 base wage, health benefits, and lower rents during the non-picking season. Due to the variation of the size of the trees and the grade and quantity of fruit in them from orchard to orchard, Warren F. Wegis, manager of the Ventura County Citrus Growers Committee, claimed it virtually impossible for the growers to determine the wage rate in advance.

Ben Aparicio, a Moorpark College student and a part-time picker in the orchards of the F and P Growers Association became a recognized leader of the strike. Aparicio on behalf of his co-workers also demanded from the growers a written redress of their grievances. This, the industry rejected. And as he spearheaded the protest, the management terminated Aparicio on May 29 for his demand to know the rate of pay at an orchard before the start of work.

Since the age of twelve, Aparicio worked alongside of his parents and four siblings in the orchards and fields of Southern California. As the strike continued Ben’s sister Manuela made leaflets that pronounced the demands for union recognition, improved homes, increased pay, as well as the statement of the wage rate at an orchard prior to the start of a day’s work. SPFWC also called for improved communication between managers and workers as many bosses in the orchards did not speak Spanish. And in addition to verbal abuse, other indignities fueled the resentment of workers. For example, the strikers claimed to be regularly cheated in their pay; citrus growers moreover refused to station port-a-sans in the orchards—particularly ignominious as work crews consisted of whole families, adults and children. As far as conditions outside the orchards, the SPFWC protested the high rents of the citrus association for substandard room and board at labor camps.

(Ben Aparicio and Cesar Chavez, left. Chavez with protesters, right. Ventura County Star Free-Press 1970)

On a Friday night, on July 17, 1970 Chavez addressed a packed room of devotees at the Guadalupe Church in the City of Santa Paula to announce the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee’s enlistment of Ventura County citrus workers as dues-paying members. In addition to these new unionists, another 350 signed cards that declared their desire to be represented by the UFWOC. Organizers achieved this after two years of work in the county. Arthur S. Gomez, the Ventura County UFWOC spokesperson, subsequently announced the intention of Chávez to address the community at Santa Paula’s La Casa Del Mexicano at 218 South 11th Street at a later date to thank the Ventura County community for its “moral and material” support during the five year grape boycott. Chavez also wished to listen to the grievances of citrus strikers in Fillmore. Although he ultimately canceled his visit due to contract negotiation in Delano, media coverage signaled his union’s intent to expand its influence in Ventura County.

In anticipation of Chavez’s next visit, the Oxnard Press-Courier noted his CSO history in the county. In fact, the specter of the tumultuous 1941 Ventura County Citrus Strike loomed in the background of the Fillmore labor dispute. A July 26 report in the Ventura County Star-Free Press fictionalized a 12 year old Chavez with a picket sign during the’41 strike even though his family had left the area over two years before. Los Angeles attorney for the Fillmore growers recalled his own work in 1941 on behalf of Charles C. Teague, president of the Ventura County Fruit Growers Exchange and founder of the brutal Associated Farmers.

At the harvest season’s peak, four thousand citrus workers, mostly men, but also women, girls, and boys, labored in the orchards of Ventura County. But this season, a good proportion struck. Gomez, also a member of Friends of the Farmworkers, informed the press that citrus pickers in Rancho Sespe and Rancho De Los Campanos, as an act of sympathy for their Fillmore brethren, left the orchards. Hence, the number of strikers grew from approximately 350 originally to 500 in the Santa Clara Valley. By July 19, 1970, an estimated number of two thousand citrus workers refused to work. To complement the walkout, a hundred and eighty people picketed the Fillmore Citrus Association at the start of each day.

(Bob Borrego, father of Diana, far right. Friends of the Farmworker, Farmworker Movement UC San Diego Online Gallery)

To raise the profile of this labor struggle, before the rise of dawn on Wednesday July 22, 1970, Chavez marshaled a procession from the F and P Growers labor camp in Fillmore to an orchard in the neighboring community of Piru to draw workers from the orchards. The march consisted of fifty men, women, and children. As they shouted, “Viva la huelga!,” the group implored pickers to join them. Overtime, the obstinacy of the capos of the citrus industry began to waver. As Chavez rallied supporters throughout Ventura County, Russel Hardison, president of the Fillmore Citrus Association, declared the intention of the grower class to extend a paid annual vacation benefit as well as the establishment of the pay rate for an orchard before the commencement of each work day. To the press, Hardison claimed that prior to the strike the grower class intended to raise the wages of workers as well as provide a vacation benefit. He went on to contest the charge that the industry charged exorbitant rents to its workers for substandard residences. In fact, the growers created 28 new residential units and remodeled 55 existing homes. The rent for newer units cost $55 a month and the older homes ranged from $30-$35. Additionally, the camp owners, they claimed, provided free water and trash removal services.

From the Aparicio home, the strikers rejected the concessions of the Fillmore Growers Association as it did not include the demands to recognize the UFWOC as their bargaining agent, improved sanitation at job sites, and the appointment of bilingual field bosses. Although citrus workers desired UFWOC representation, extant labor law (i.e, the federal National Labor Relation Act) did not apply to field or orchard workers, only shed packers. After thirteen days, the strike ended on Wednesday July 29, 1970. In exchange for paid vacation based on the hours worked during a year and the statement of wage rates at orchards before the start of work, the strikers surrendered the demand to have the UFWOC recognized as their bargaining agent. So the harvest of Valencia oranges in Fillmore, Moorpark, and Piru resumed. As usual, to save some face, the citrus industry claimed no crop losses due to the walkout. Despite this denial, the partial labor victory in Fillmore gripped the attention of the larger grower class. Consequently, toward the end of August 1970, the Matilija Growers Association in the Ojai Mountains of the county announced its decision to grant forty hours of paid vacation after the completion of nine hundred hours of orchard work in a year.

This is just one action to be featured in Chicano On!

Legacy.

In closing, the legacy of the movement of Chicanas and Chicanos continues to this day. This is by the fact that a “hard core” number of Moorpark College, Ventura, CSUN, UCLA, and UCSB alumni played a critical role in the demand for Chicana/o Studies at California State University Channel Islands. This is to say, these individuals continued the moxie of the movement of Chicanas and Chicanos so that subsequent generations would do so into the future.

C/S

fpb

Tuesday, August 8, 2017

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)