Sunday, December 2, 2012

Is there a doctor in the house?

When I was an undergraduate at California State University, Fresno my mentor Dr. Chang commented that UC Berkeley professors are generally not addressed as Dr. This remark was in response to the insistence of specific colleagues of his to be called doctor. At Berkeley, it was a given that the professors were PHDs. In fact, even the department secretaries there had PHDs, he stated facetiously.

Nonetheless, I called my professor Dr. Chang out of respect for his position. Especially being that he was one of a few historically underrepresented faculty at Fresno State. It also had a nice ring. Sort of like Dr. Sun Yat-sen, Dr. King, Dr. George I. Sanchez, etc.

When I recognize ethnic and racial minority academics or professional doctors with the Dr. handle it is not out of a fascination with elitism (well maybe a little) but to acknowledge their exceptional accomplishment in a society of unequal educational opportunity. I, myself, do not insist on being called Dr., but if I am I will not object. I do, however, feel uneasy being recognized as such in the case that there were a medical emergency where I may find myself and someone pleading, “IS THERE A DOCTOR IN THE HOUSE?!” I could perform the Heimlich maneuver in the case of a person choking or cpr for a cardiac arrest—btw: is it 5 chest compressions per breath or 7?

I participate in the graduation ceremonies at California State University Channel Islands to serve as an example to students, particularly Chicanas/os, of the possible. I gladly pose with graduates as I imagine many never before viewed a Chicano in doctoral regalia.

When I graduated from Fresno State, I was impressed by the pomp and circumstance of the faculty procession into Bulldog stadium. I knew then that I wanted some day to be a part of that parade. Now I am and realize how actually few people of color are in such painted pageants.

As I was struggling to complete my dissertation, I posted a picture of the Claremont Graduate University’s doctoral regalia for inspiration. The pursuit of a PHD was not based on potty intentions but the desire to serve as a presumed voice of authority in my community when needed. Nor did I feel that being an academic was a professional career that would separate me from my working-class roots. As long as I depend on a wage, I will always be of the proletariat in solidarity with other workers, many with no degrees who make far more than I will ever realize.

Con Safos

fpb

Sunday, September 30, 2012

Eulogy for an Activist

Ventura County recently lost a person who provided a media voice to the Latino community since the 1960s. He was Javier R. Santana — journalist, civic activist, mentor and, as one of his longtime friends characterized him, a "true revolutionary" for the cause of the people.

When Oxnard High School student Nelly Medrano called his Santa Paula KPSA radio show in 1964 expressing interest in a career in broadcasting, Santana offered to assist her. As her mentor, he taught her public communications and helped her get accepted to UCLA.

In the tradition of legendary broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow, Santana believed that an informed citizenry led to the creation of a better future. Therefore, at a time when Latinos were virtually nonexistent on college campuses, Santana championed higher education opportunities on his radio show so the next generation of Latinos could tackle issues of the day.

He also supported young Chicano movement activists who charged the Oxnard Police with harassment and the brutalization of La Colonia barrio residents.

In 1968, when sagacious Brown Berets appealed to the City Council to redress their grievances — they demanded a Police Department investigation by the state attorney general and the creation of a community review board — Santana recognized that this cadre of young men and women was the leadership of the future and urged the Ventura County Community Service Organization to support them.

Santana was prescient as many Brown Berets and other students he mentored and supported graduated from college on their way to becoming pillars of the community as social workers, educators, peace officers, elected officials and entrepreneurs.

As a radio commentator at KOXR "La Mexicana," from 1965 to 1993, Santana hosted a live program titled, "El Pueblo Opina (The People's Opinion)." It was on this evening show that Spanish-speaking community members discussed issues of school segregation, César Chávez and the United Farm Workers union, the county's labor history, politics, immigration, poverty, public health and discrimination.

As the Latino community was, and continues to be, diverse related to time of residency, class status and education, parents, guests and callers engaged in debates, often heated, as Santana moderated his radio show.

In one instance, Santana helped United Farm Workers organizers convince the KOXR ownership to provide airtime to create a program titled "La Hora del Campesino (The Farmworker Hour)." The show helped the UFW organize for a strawberry strike in 1974.

During this labor protest, the Sheriff's Department flew a helicopter closely above a UFW picket line in El Rio. When the protesters responded in their defense they were arrested. A public outcry combined with the coverage by Chicano journalist Frank Del Olmo of the Los Angeles Times, support from county Supervisor John Flynn and Santana's actions in and out of the radio booth, influenced the sheriff's department to cease such acts.

This was the type of news English-language media generally did not cover. And if they did report such stories, it was not from the point of view of the Spanish-speaking community.

Santana also understood the importance of culturally affirming events to inspire positive change. He partnered with restaurateurs such as the Casa Tropical to feature an amateur hour talent contest that he emceed. Winners went on to perform live on his radio program.

One contestant was Alicia Lopez Juarez, who went on to produce 21 albums, star in nine movies and, on top of performing for Latin American presidents, married the legendary mariachi singer-songwriter José Alfredo Jiménez.

Santana joined the movement for greater minority representation in an unsuccessful bid for a seat on the Oxnard City Council in 1974. He did not win, but three years later the council appointed him to the Community Relations Commission. As a candidate, commissioner and radio personality, Santana made sure that the interests of the Latino community were heard.

During the 1990s, Santana continued to give voice to the underserved on the bilingual television program "Santana En Vivo/Santana Live." The show aired throughout Southern California and discussed topics he had covered since 1965 in "El Pueblo Opina."

As he did from the start of his broadcast journalist career, Santana promised callers and guests the opportunity to voice their perspectives, irrespective of their language fluency or political ideology.

He leaves a legacy that many who knew and heard of him will seek to continue.

Javier Santana, with his passionate and golden voice of hope and defender of justice, will forever remain "The Voice for the Latino Community."

Frank P. Barajas

Jess Gutierrez

Image provided by Jess Gutierrez

This essay was published by Amigos805 and the Ventura County STAR.

Sunday, August 19, 2012

Dead End In Norvelt

The project of getting our kids prepared for a university of their choice involves reading time together. The first book completed in this endeavor this summer was E.B. White’s 1952 classic, Charlotte’s Web. Immediately thereafter, we started Jack Gantos’s 2012 Newbery Award winning Dead End In Norvelt. The story is situated in the Cold War era of the 1950s and makes frequent reference to the New Deal. In fact, the name of the Midwestern town of Norvelt is a derivation of Eleanor Roosevelt who promoted the creation of affordable housing for the working class. Miss Volker, a nurse and devotee of Roosevelt, promised to write an obituary for each of the original residents before leaving.

Gantos embeds historical commentary related not only to the New Deal and the McCarthy Era but also the New Immigration of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and World War II, at home and abroad. In reading the story to my traviesos (mischievous children), I restrained myself from explaining the historical landscape detailed by the author in order not to interrupt the flow of the narrative.

Like White’s Charlotte’s Web, Gantos adroitly complements the personalities of the characters to amplify the forces at work. For example, Jack Gantos, who is also the name of the main character, is a nosebleed prone adolescent in search of purpose, and comes to appreciate the power of the written word, history, and ideas. He learn this during his assignment to assist the valetudinarian Miss Volker stricken with arthritis and unable to write the obituaries accompanied by “this day in history” analects.

Jack’s father, a WWII veteran who served in the Pacific theater, views the world through a Manichean lens of the Cold War. Dad prepares a bomb shelter for his family to survive an inevitable nuclear Armageddon. He also refers to Miss Volker as a Commie for her devotion to the New Deal. Public employees are also Commies in his eyes. In many ways, Jack’s father is a Babbitt of the variety within the writings of Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, and H.L. Mencken.

The dying town of Norvelt is also a largely white community. White residents denied the Jeffersonian, middle-class dream of homeownership to black migrants. It was only when the Roosevelts were moved by the appeal of one black family that an accommodation was made. Mrs. White, the wife and mother of the only black family in town, advanced the naming of the town founded during the Great Depression in tribute to Eleanor Roosevelt.

In finishing the book, Jack Gantos validated my belief that the line between fact and fiction can be artificial. Many places like Norvelt exist that are, in the words of Gantos, off-kilter “where the past is present, the present is confusing, and the future is completely up in the air.”

Con Safos

fpb

Saturday, August 11, 2012

To Swim or Not To Swim

To graduate from Marine Corps Recruit Training, prospective Marines must pass a swim/survival test. In the summer of 1985, I failed it twice before qualifying. The second time my lungs filled with water and flowed out of my mouth as I lay prostrate on the side of the pool deck unassisted. As I coughed up the remaining liquid from the pit of my stomach, the swim instructor barked that I had fifteen minutes to get back in the water. The third try was the charm. I passed. But as I looked over to the far side of the pool, I saw a distinct class for recruits who could not pass after the third try. The overwhelming majority of them were Chicano/Latinos and African Americans. In a New York Times opinion essay, Martha Southgate provides an informative perspective as to the reasons why high proportions of people in poverty and of color, especially African Americans, tragically don’t know how to swim.

Con Safos

fpb

Sunday, August 5, 2012

Oxnard College Past and Present

For my study of the Chicano Movement in Ventura County, I learned that before Oxnard College’s opening in 1975, Vietnam veterans and newly minted high school graduates from the Oxnard Plain rode buses to Moorpark College because the largest city in Ventura County did not have a community college.

After their transfer to and graduation from San Fernando Valley State College (now California State University at Northridge), the University of California at Santa Barbara, or other universities, they entered careers as educators, entrepreneurs, public servants, and healthcare and law enforcement professionals.

The spirit of the Chicano Movement also inspired the filing of the Soria, et. al. v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees case in which federal Judge Harry Pregerson issued a 1971 summary judgment that ordered the district to develop a plan of desegregation.

An appeal of Judge Pregerson’s ruling uncovered additional evidence that proved that since the early twentieth century the school district obsessed over the creation of policies to segregate students of Mexican origin.

The remedy mandated busing. The school board and parents bitterly resisted the order. Many white parents moved their families out of Oxnard to avoid having their children bussed to schools in the barrio community of La Colonia. Oxnard College could have benefited from the political clout that left with them.

The development of Oxnard College was further stunted by the 1978 passage of Proposition 13, the property tax initiative that shrunk the coffers of public institutions.

As a result of Proposition 13 and our recent great recession, the vision of the California Master Plan of Higher Education has faded to near oblivion. Students are again traversing roads to attend community colleges with remnant academic and vocational programs in their pursuit of a middle class life.

Even before Proposition 13, Oxnard College’s growth as a startup depended on the decisions of a district board that found itself in the position of having to divide funds three ways. Understandably, the presidents of Moorpark and Ventura College advocated strongly on behalf of their campuses.

After graduating from Oxnard High School in 1983 I carpooled to Moorpark College since Oxnard College did not have a wrestling program. In fact, many Oxnard Union High School District graduates also traveled to Moorpark or Ventura due to Oxnard College not enjoying a comprehensive athletics program.

This disadvantaged Oxnard College’s development and benefited the other two campuses as funding is based on the number of Full Time Equivalent Students (FTES) registered for 12 or more units of coursework.

Along with a tacit anti-Mexican sentiment in the county, the above explains why Oxnard College’s support services, academic programs, and the aesthetics of its facilities were inferior to the campuses of Moorpark and Ventura.

Until the passage of Measure S in 2002, some five buildings, surrounded by desolate fields, defined Oxnard College. Its curb appeal alone was enough to turn away students.

When the board deliberated on the apportionment of some $356 million from the Measure S bond, the initial plan was to allocate Oxnard College only $60 million. The rationale was the institution’s smaller student population. Consequently, it deserved a lesser cut.

Hence, the conundrum: a smaller campus with the highest proportion of students of African, Filipino, and Mexican origins deserved disparate support, precluding the expansion of course offerings that translated to students of the Oxnard Plain commuting to Moorpark and Ventura.

When Area 5 Ventura County Community College District Trustee Arturo Hernandez demanded that Measure S funds be allotted equitably the board reconsidered its original distribution.

This is the history that backdrops the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges reports.

In resisting the further evisceration of programs, Trustee Hernandez has been castigated by the commission for his advocacy on behalf of all students, including those at Oxnard College. This is ironic. The ACCJC’s own Accreditation Standards charges trustees with the duty to ensure that the district provides for the “fair distribution of resources that are adequate to support the effective operations of the colleges.”

But when Trustee Hernandez performed his due diligence, posed questions of equity for the three colleges, he was rebuked by not only the accrediting body but also the VCCCD’s outgoing chancellor, James Meznek, in a crafty letter leaked from his office, and a patronizing STAR editorial. Trustee Hernandez, the most senior member of the board, was ordered to stand down.

I appreciate Trustee Hernandez’s concern for district-wide equity. He proved this to me in 2009 when he listened to Moorpark College alumni who unsuccessfully attempted to save the district’s remaining wrestling program.

Despite the characterization of the issues by the STAR, one member of the board does not determine the accreditation of a college district. The STAR must educate itself on the realities of accreditation and investigate the hearsay allegations against Trustee Hernandez.

Con Safos

fpb

PS: A version of this essay was run in the Ventura County Star on August 12, 2012

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

The Wizard Behind the Curtain: Walter Cronkite

At Fresno State I majored in History in the mid ’80s. While there, I befriended fellow students from San Joaquin Valley agricultural communities—as though there were any other kind—such as Firebaugh, of course Fresno, Madera, Mendota, Merced, Parlier, Reedley, and Three Rocks. “Three Rocks! Where the hell is Three Rocks?” I said to Ralph shortly after meeting him. He couldn't tell me. I imagined three stones out in the middle of nowhere.

One reason I was drawn to Fresno State was due to my misguided assumption that there would be many Chicano students. After all, the university was in the middle of ag. land. Later I came to understand that I would have been better off in this regard attending a university nearer Oxnard like CSUN or Cal. State L.A. But neither had a wrestling team so that was not going to work.

As I signed up for classes on a catch as catch can manner, I took Constitutional Law because Chicano friends Gene, Jaime, and Anthony majored in Political Science and Public Administration. I liked hanging with them and Constitutional Law was related to US History, so I took both sections just because I liked their company.

One evening we studied a Supreme Court case on the powers of the presidency during the 1960s. I don’t remember the case but it led to the professor’s interminable talk on the presidencies of John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and the Vietnam War. At one point, the professor rhetorically asked the class of about six, “When did the US public stop supporting the war in Vietnam?” The professor pushed up his glasses with his index finger as he panned the faces of all six of us. Then Gene raised his hand. Anthony, Jaime, me, and the other two students shifted our heads to Gene in surprise. Gene then said it was in February of 1968 when Walter Cronkite reported from Vietnam during the evening news that the US was not winning the war as told by the military. At best it was a stalemate. Gene stole the professor's thunder. He could only stoically affirm Gene's answer before letting us out for a break.

We escorted Gene in triumph to get coffee as we asked how he knew the answer. With a big grin he confessed: “The more Professor B went on, the more I realized that he was recounting the PBS documentary I was watching the other night on the Vietnam War. One scene showed Walter Cronkite declaring that the US was not winning the war.” We laughed. And it was hard to keep a straight face when we returned to the second half of that class meeting.

Authority and power is based on the possession of knowledge. This is the central point I learned in Con Law.

Con Safos, fpb

Saturday, June 30, 2012

Enter The Pit: Diary of a Husky Kid II

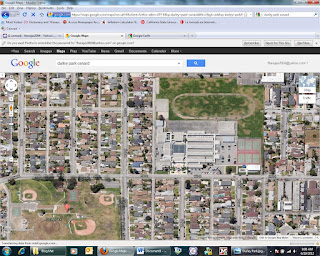

Image: Durley Park at the bottom left and Haydock Jr. High at the top right. Click on image for a closer look.

As to the main title, this is not a recount of my days as a folk style wrestler as the center of a mat is known as such. But rather it speaks to an arena frequented by middle schoolers of Haydock Jr. High during the 1970s (1). When an insult or challenge arose in the hallways or on the playground between two boys or girls, a pause in the confrontation took place. Rather than fight it out for it to be quickly broken up by teachers and face punishment by the principal, the two foes agreed to meet at the nearby Durley Park to settle a score uninterrupted.

Staying away from trouble was a lesson my old man tried to instill in me. When sirens ended at a car accident or fire near our home on I Street, my dad had us watch from afar when the neighbors walked up close to the scene. But one day I disregarded this teaching when two of my Haydock Jr. High classmates where going to have it out after school at “the pit” of Durley Park. From the throwing down of the gauntlet to the final school bell, the whole school knew of a pending fight. Walking west on Hill Street from campus to the Durley Park pit, each side had an entourage of supporters.

Usually, when I followed my classmates to one of these periodic, yet regular, contests, I safely observed downward from the ridge of “the pit.” I understood that I risked getting into trouble if I got too close. But one day I decided to disregard my dad’s admonishment of staying a distance away from fights when all others looked on closely. As I jostled through the crowd to see the brawl, I pushed back someone who gave me stiff shove. It was Jimmy H. He was a short, skinny kid who had a reputation for being a street tough. I never saw him fight but people feared him because he talked and walked threateningly. You didn’t mess with Jimmy. He also had an older brother that looked meaner, and uglier.

After I pushed Jimmy, he responded with f%#$ you punk before he began to wail his fists. Before his attack, I did what my dad showed his husky, wannabe cholo, Chicano kid. I got into my boxing stance and raised my dukes, one fist slightly in front of the other. Soon we were at where most street fights end up: on the ground. I took advantage of my girth to straddle Jimmy H’s chest while I unremittingly pummeled his face. It was though I was unleashing pent up rage. All of a sudden, from the corner of my right eye I saw a black biscuit shoe headed toward my face before it knocked me off Jimmy H. It was the foot of his older, fouler brother, Michael. Dazed I got up and the fight was over. Maybe Michael understood that if he went for me a possible larger melee would break out—who knows?

Anyway, I was sort of the hero the next week as I heard classmates talk how I stood up to Jimmy H. and won. From then on, I was one of the kids in school that others thought twice about tangling with, except for Jimmy H. Every time we met in the hallway or at the park he’d challenge me by calling me punk as if he won our last and only fight. I never understood this. Never taking my eyes off of him (2), I always said no to his invitation to a rematch.

But what I did from then on was to stay far away as possible from street fights, except when I was backing up one of my friends.

1. I have been told that to this day the pit is the site of similar match ups.

2. My dad also told me to never turn your back on your enemy.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

School Segregation: Not Just Black and White

Image: Cesar Chavez, Odessa Newman, Juan Soria

California school districts segregated children of Mexican origins in California for much of the twentieth century. Like in Oxnard, school boards held that this segregation was a de facto (unofficial) manifestation of discriminatory residential developments that instilled covenants within deeds prohibiting the sale of homes to non-whites. But as the appeals process of the Soria v. Oxnard School District case (1971) revealed, the segregation of children of Mexican origins was obsessed upon by school boards in the early twentieth century. A classic film detailing this phenomenon in San Diego, California is the docudrama The Lemon Grove Incident. In this true story, Mexican parents fought against this discrimination in 1931 and won.

School segregation did not just mean separate schooling but also the inferior education of children of Mexican origins within substandard facilities. As a result, unequal opportunity started early in the lives of students of Mexican origins. The legacy of de jure (legislative) school segregation also affected the life chances (i.e., higher education prospects, professional career opportunities, property ownership, well-being, and the inter-generational passing of wealth) not only of those who had been segregated but also their progeny. In fact, student achievement from kindergarten to the university is linked to the household income based on life chances. This is the cycle.

This historical issue is personal for two reasons. First, in 1971 I was a first grader in the Oxnard School District and was bussed to el norte (the Anglo and more middle class part of Chiques) due to the Soria case. At the time, I did not know why my neighborhood friends and I were bussed across town. Classmate who wondered may still not know why they were bussed but I do. And even when I attended an integrated high school, I noticed that about half of my Mexican origins peers either dropped out after their freshman year or took non-college prep courses.

The second reason the educational hamstringing of students of Mexican origins is significant is because of my old man’s stories of living in the segregated city of Santa Paula during the 1940s. This community was, and to a large degree still is, divided by rancher families and agricultural workers, white theater patrons and the Mexican section, white churches and Mexican iglesias. This separation was so mundane that people in communities in and out of Ventura County internalized the mores of the divided societies in which they lived. Growing up, my father would tell me how when he was in high school most Mexican students took shop classes. So he encouraged me to take college prep courses at Oxnard High.

I often wonder how different the life chances of the majority of my extended family members and classmates of Mexican origins would have been if it had not been for the segregation policies in Ventura County. Would more of them be doctors, lawyers, or scientists rather than being chronically ill or ensnared in the criminal justice system for a large part of their lives? Would they have been upper level managers living in solidly middle class communities rather than taking orders and living in neighborhoods with overcrowded and underfunded schools? Would they have discovered cures instead of being victims of industrial petro chemicals?

Read any scholarly study on the demographic character of our nation’s schools and you will discover that the dynamics of segregation are to a greater extent still with us today. And there seems to be no answer to the residential flight from the presence of people of color and their school-aged children.

Con Safos

fpb

Thursday, March 8, 2012

The Sunbelt Strategy

What do California State University Professor Rodolfo F. Acuña, Henry David Thoreau, and Abraham Lincoln have in common? Before I tell you, you need to know that the narratives of Acuña (a founder of Chicano Studies and author of the seminal text in this field, Occupied America), Thoreau, Sandra Cisneros, William Shakespeare, and others have been banned from the classrooms of the Tucson Unified School District as part of the state of Arizona’s dismantling of a Mexican American Studies (MAS) program.

The MAS program once taught 1500 students. Its approach of integrating the heritage of Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Mexican Americans increased the graduation rates of students of Mexican origins while preparing them for college.

Tom Horne, Arizona’s former superintendent of public Instruction and now the state’s attorney general, spearheaded the attack on MAS by way of the passage of HB 2281. This campaign was so effective in tapping into the anxieties of Arizonans concerned with the rising presence of people of Mexican origins that a host of Republican politicians jumped on the Republican Sunbelt Strategy. “The Sunbelt Strategy?” you may think.

This is a version of Richard Nixon’s 1968 Southern Strategy refined by his campaign strategist Kevin Phillips. This plan appealed to the predominantly Democratic white electorate of the South disaffected by the civil rights gains of African Americans. This played out in President Nixon’s equivocations on Affirmative Action and school desegregation. The Southern and Sunbelt states of Arizona and Texas being a Red region today illustrates the efficacy of this Machiavellian ploy.

This history helps us understand why Horne, his successor at the office of the superintendent of public instruction, John Huppenthal, and other Arizona Republican pols, including Governor Jan Brewer, have jumped on the band wagons of anti-MAS and anti-immigration. No matter that MAS has been proven to be pedagogically effective and the entrance of immigrants from Mexico has plummeted in recent years (according to the Mexican Migration Project at Princeton and the Pew Hispanic Center).

To justify his canard on MAS, Horne contends that the program promotes the overthrow of the United States government and advocates ethnic solidarity. But a curriculum audit by the Cambium Learning Corporation, paid for by Huppenthal’s office, found that the MAS program did neither.

The audit also recognized how MAS students outperformed their peers not in the program in regards to test scores and graduation. It did this by making learning culturally relevant to students of all backgrounds.

So the real reason why Horne has attacked the MAS program is to create yet another wedge issue to provoke Republican voters to go to the polls.

In the history of the United States, the use of xenophobia by politicians of the likes of Horne and Huppenthal has been politically expedient. In the late 19th century, Denis Kearney, who himself was an Irish immigrant, scapegoated Chinese immigrants for the demise of the economic status of white workingman, among other things such as the lurid notion that they seduced white women with the use of opium.

Successive financial panics and depressions of the 1870s to the 1890s stoked the distress of people. Across the nation politicians of both the Democratic and Republican parties attempted to outdo each other in their anti-Chinese rhetoric, despite the fact that less than 1 percent of the population was Chinese in the US. This hysteria led to the passage of a series of Chinese Exclusion Acts and ultimately the exclusion of all Asian immigration by 1924.

Even before the popular understanding of the Southern Strategy, when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights bill of 1964, it is purported that he stated to his aides that with a stroke of his pen he ostensibly delivered the white electorate of the South to the Republican Party.

Now vast parts of the South, the Midwest, and the Sunbelt states are controlled by the Republican Party by its manipulation of wedge issues around Affirmative Action, bi-lingual education, contraception, gay marriage, immigration, and now Mexican American Studies in Arizona.

So what do Acuña, Thoreau, and Lincoln have in common? All three looked closely at the start of the Mexican American War of 1846-48 and came to the conclusion that it was an invasion of Mexico’s sovereignty to conquer the Southwest. Second to the exploitation of yet another wedge issue for political advantage, perhaps this is exactly the sort of history that Horne and the Arizona Republican party leadership do not want Mexican American Studies students of the Tucson Unified School District to learn.

Con Safos

fpb

Ventura County Star

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)