Saturday, June 30, 2012

Enter The Pit: Diary of a Husky Kid II

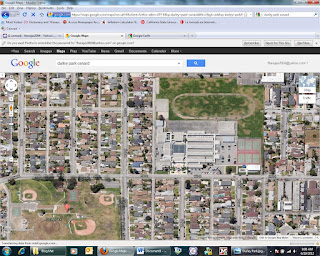

Image: Durley Park at the bottom left and Haydock Jr. High at the top right. Click on image for a closer look.

As to the main title, this is not a recount of my days as a folk style wrestler as the center of a mat is known as such. But rather it speaks to an arena frequented by middle schoolers of Haydock Jr. High during the 1970s (1). When an insult or challenge arose in the hallways or on the playground between two boys or girls, a pause in the confrontation took place. Rather than fight it out for it to be quickly broken up by teachers and face punishment by the principal, the two foes agreed to meet at the nearby Durley Park to settle a score uninterrupted.

Staying away from trouble was a lesson my old man tried to instill in me. When sirens ended at a car accident or fire near our home on I Street, my dad had us watch from afar when the neighbors walked up close to the scene. But one day I disregarded this teaching when two of my Haydock Jr. High classmates where going to have it out after school at “the pit” of Durley Park. From the throwing down of the gauntlet to the final school bell, the whole school knew of a pending fight. Walking west on Hill Street from campus to the Durley Park pit, each side had an entourage of supporters.

Usually, when I followed my classmates to one of these periodic, yet regular, contests, I safely observed downward from the ridge of “the pit.” I understood that I risked getting into trouble if I got too close. But one day I decided to disregard my dad’s admonishment of staying a distance away from fights when all others looked on closely. As I jostled through the crowd to see the brawl, I pushed back someone who gave me stiff shove. It was Jimmy H. He was a short, skinny kid who had a reputation for being a street tough. I never saw him fight but people feared him because he talked and walked threateningly. You didn’t mess with Jimmy. He also had an older brother that looked meaner, and uglier.

After I pushed Jimmy, he responded with f%#$ you punk before he began to wail his fists. Before his attack, I did what my dad showed his husky, wannabe cholo, Chicano kid. I got into my boxing stance and raised my dukes, one fist slightly in front of the other. Soon we were at where most street fights end up: on the ground. I took advantage of my girth to straddle Jimmy H’s chest while I unremittingly pummeled his face. It was though I was unleashing pent up rage. All of a sudden, from the corner of my right eye I saw a black biscuit shoe headed toward my face before it knocked me off Jimmy H. It was the foot of his older, fouler brother, Michael. Dazed I got up and the fight was over. Maybe Michael understood that if he went for me a possible larger melee would break out—who knows?

Anyway, I was sort of the hero the next week as I heard classmates talk how I stood up to Jimmy H. and won. From then on, I was one of the kids in school that others thought twice about tangling with, except for Jimmy H. Every time we met in the hallway or at the park he’d challenge me by calling me punk as if he won our last and only fight. I never understood this. Never taking my eyes off of him (2), I always said no to his invitation to a rematch.

But what I did from then on was to stay far away as possible from street fights, except when I was backing up one of my friends.

1. I have been told that to this day the pit is the site of similar match ups.

2. My dad also told me to never turn your back on your enemy.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

School Segregation: Not Just Black and White

Image: Cesar Chavez, Odessa Newman, Juan Soria

California school districts segregated children of Mexican origins in California for much of the twentieth century. Like in Oxnard, school boards held that this segregation was a de facto (unofficial) manifestation of discriminatory residential developments that instilled covenants within deeds prohibiting the sale of homes to non-whites. But as the appeals process of the Soria v. Oxnard School District case (1971) revealed, the segregation of children of Mexican origins was obsessed upon by school boards in the early twentieth century. A classic film detailing this phenomenon in San Diego, California is the docudrama The Lemon Grove Incident. In this true story, Mexican parents fought against this discrimination in 1931 and won.

School segregation did not just mean separate schooling but also the inferior education of children of Mexican origins within substandard facilities. As a result, unequal opportunity started early in the lives of students of Mexican origins. The legacy of de jure (legislative) school segregation also affected the life chances (i.e., higher education prospects, professional career opportunities, property ownership, well-being, and the inter-generational passing of wealth) not only of those who had been segregated but also their progeny. In fact, student achievement from kindergarten to the university is linked to the household income based on life chances. This is the cycle.

This historical issue is personal for two reasons. First, in 1971 I was a first grader in the Oxnard School District and was bussed to el norte (the Anglo and more middle class part of Chiques) due to the Soria case. At the time, I did not know why my neighborhood friends and I were bussed across town. Classmate who wondered may still not know why they were bussed but I do. And even when I attended an integrated high school, I noticed that about half of my Mexican origins peers either dropped out after their freshman year or took non-college prep courses.

The second reason the educational hamstringing of students of Mexican origins is significant is because of my old man’s stories of living in the segregated city of Santa Paula during the 1940s. This community was, and to a large degree still is, divided by rancher families and agricultural workers, white theater patrons and the Mexican section, white churches and Mexican iglesias. This separation was so mundane that people in communities in and out of Ventura County internalized the mores of the divided societies in which they lived. Growing up, my father would tell me how when he was in high school most Mexican students took shop classes. So he encouraged me to take college prep courses at Oxnard High.

I often wonder how different the life chances of the majority of my extended family members and classmates of Mexican origins would have been if it had not been for the segregation policies in Ventura County. Would more of them be doctors, lawyers, or scientists rather than being chronically ill or ensnared in the criminal justice system for a large part of their lives? Would they have been upper level managers living in solidly middle class communities rather than taking orders and living in neighborhoods with overcrowded and underfunded schools? Would they have discovered cures instead of being victims of industrial petro chemicals?

Read any scholarly study on the demographic character of our nation’s schools and you will discover that the dynamics of segregation are to a greater extent still with us today. And there seems to be no answer to the residential flight from the presence of people of color and their school-aged children.

Con Safos

fpb

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)